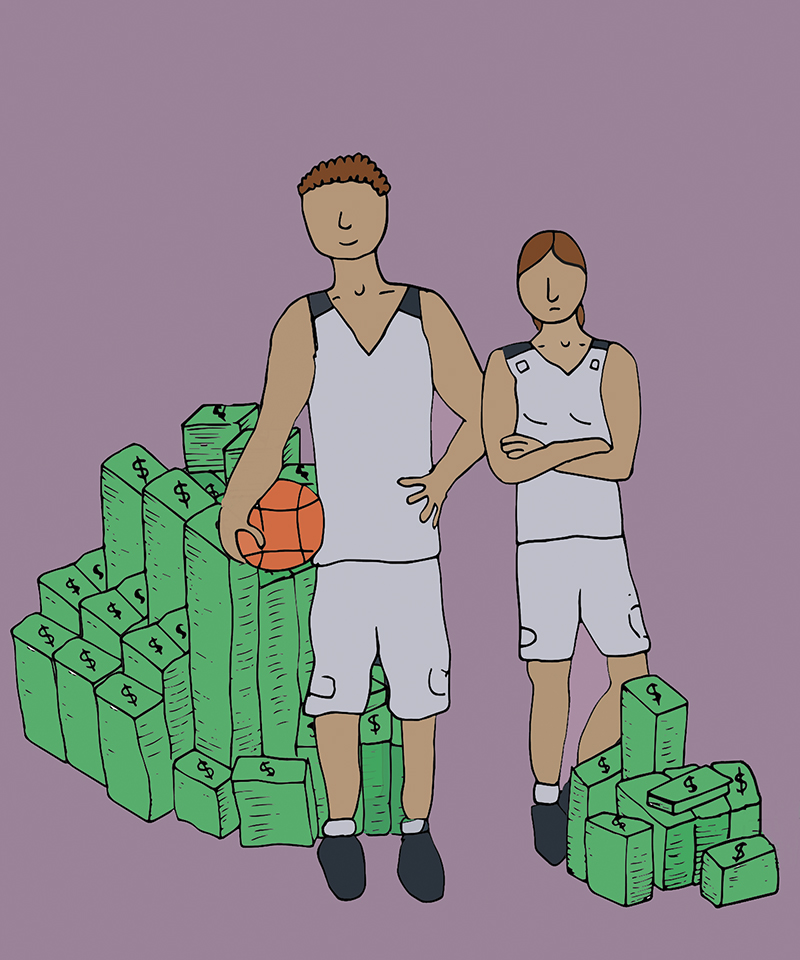

Highest NBA salary 561 times the average female player

In 2018, the average NBA player made an annual salary of just over $7.1 million, according to Sporting Intelligence. The average WNBA salary is a fraction of that total, at just over $71,000, according to Forbes.

Incredibly, both of these salaries pale in comparison to the NBA supermax deals implemented after the 2017 season. This rule allowed three-time NBA Champion and two-time MVP Stephen Curry to sign an enormous five-year, $201 million deal. That’s an average of $40.2 million per year, nearly six times the average NBA salary and 561 times the average WNBA salary. Do these supermax deals exist for female superstars?

Sylvia Fowles, the 2017 WNBA MVP, made $109,000, while her MVP male counterpart, Russell Westbrook, made $28.5 million. These salary increases have prompted many women from the WNBA to speak out on social media about the wage gap.

154M ……….. must. be. nice. We over here looking for a M 🙃 but Lord, let me get back in my lane pic.twitter.com/IFDZLlI53z

— A’ja Wilson (@_ajawilson22) July 2, 2018

The gap between male and female wages has been a long-standing debate, but is there a true solution? In the entertainment and sports world, it’s not about what you perceive you are worth, but what you can leverage through negotiations. The value of a sports league only increases if it is consumed by the public. Since the WNBA started play in 1997, attendance has steadily decreased. From 2017 to 2018, the league attendance went down by 13 per cent. How does this harsh reality affect the women whose passions exist in the world of sports?

Third-year and fifth-year Concordia Stingers guards Caroline Task and Aurélie d’Anjou Drouin believe the WNBA players made comments about the wage gap because of the NBA’s supermax deals.

“If a girl wants to go pro here and make a living out of it, you have to go play in Europe; you can’t even stay in North America,” Task said. “I think it has a huge impact on girls wanting to go pro.”

For female athletes, choosing to pursue a professional career is risky, with a chance of not making it. Even if they do, the pay could be minimal. But that won’t stop Task.

“Personally, if I had the chance obviously, I would go pro for a few years, but that’s where it comes in,” Task said. “You have to love the game that much more to sacrifice the career to play for little to no money.”

Despite her love for the game, d’Anjou Drouin expressed a different point of view. “There’s so many job opportunities here. I already have my job for next year, and it’s probably twice as much money as I would make playing basketball,” she said.

Despite their different points of view, they can both agree on the fact that at the university level at Concordia, they feel equally supported as the men.

“I think Concordia does a really good job of advertising all the games—there’s never preferential treatment,” Task said.

D’Anjou Drouin also made a suggestion on how to increase WNBA attendance. “I think that the way it works here in university is an idea that maybe could be brought to professional levels,” d’Anjou Drouin said. “Maybe if they do doubleheaders like they do at Concordia, maybe it would bring more NBA fans to the women’s games.”

Currently seven WNBA teams are in the same city as an NBA counterpart.

To accommodate this possible change, the WNBA season schedule, which plays from May to September, would have to coincide with the NBA, whose schedule runs from October to April, and has 48 extra games.

However, with the NBA players publicly supporting the WNBA through social media and attendance, this could prompt NBA fans to give the WNBA a chance. Whether the league continues to grow or not, it’s clear that the love of the game is still what drives both men and women to continue to play, regardless of financial incentives.

Graphic by @spooky_soda