To all the hashtag warriors out there who helped make Kony 2012 the most viral video in history: you’re sending the wrong message.

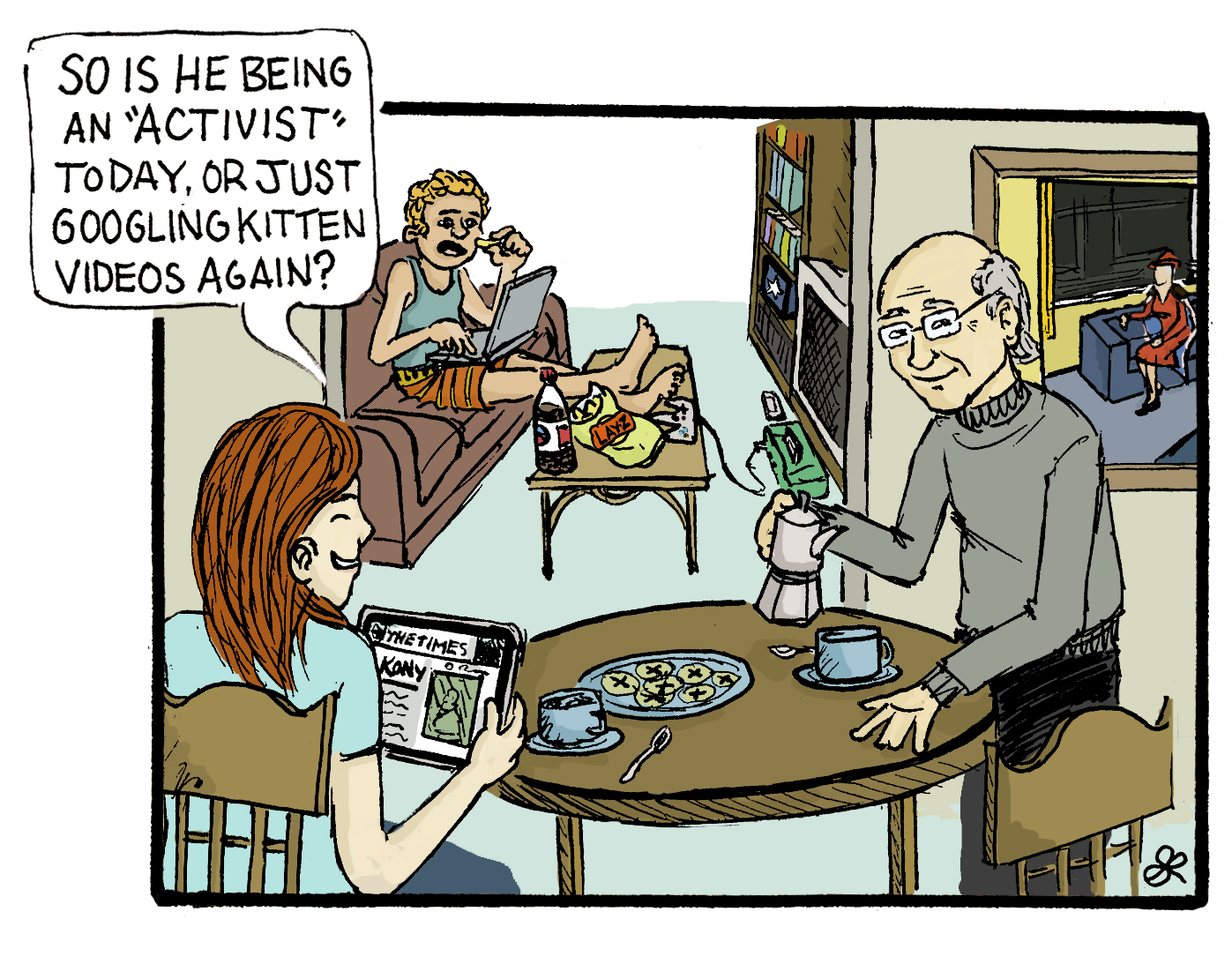

Not only did you share a video that was misleading and rife with inaccuracies, you also set a dangerous precedent. You made it alright for slacktivism, and clicktivism, to be acceptable. You missed the point of social media and its incredible potential.

Both of these philosophical concepts are derogatory for a reason. They describe Internet users who would rather perform a series of feel-good measures with no end result, rather than being truly proactive and making an effort to contribute to an important cause.

The prime example of slacktivism is the recent Kony 2012 campaign, lead by the NGO Invisible Children. Their goal was to raise awareness of Joseph Kony, the leader of a dwindling Ugandan guerrilla group. They were successful: their YouTube video has so far been watched more than 82 million times.

But how did they think they were making a difference by producing this video? Furthermore, how did they think you and I, with no military resources at our disposal, could in any way help their cause?

Osama bin Laden didn’t need the Internet to make his videos viral; he released them himself, and media outlets around the world broadcast them without hesitation. He was, by all accounts, one of the world’s most infamous people, right up until his death last year. He and Kony were both on the run, both protected by various bodyguards, and both backed by funds you and I don’t know about. Was bin Laden caught because of his notoriety, or because social media users raised awareness of the terrorist activities he was planning? Of course not.

So, Joseph Kony is a household name. Now what?

According to Invisible Children’s 30-minute collage of emotional YouTube clips, the only way you and I can affect Kony’s capture is by purchasing an “action kit”: wearing a bracelet and putting up posters on April 20. You could donate to IC, but that money would likely go towards producing another shiny video full of bells and whistles and you would actually be helping the corrupt Ugandan military, which IC publicly supports. Kony left Uganda several years ago, so what’s the point?

The key is using social media effectively. It’s shocking to see how seriously advanced our society’s attention deficit disorder is because just two months ago, we were given a perfect example of how to effectively use social media in order to bring about change: the protests against the SOPA and PIPA bills in the United States. Although I can recognize the irony here of a “lack of effort” (the Internet-wide blackout that helped shelve the bills happened because Internet users stopped going to influential websites), this was a real example of cause and effect by way of social media.

Can you imagine the effectiveness of the current protests against tuition strikes if their efforts were focused entirely online? “Hey Jean, what’s the deal, eh? I don’t want to pay higher tuition fees. #angry.” Thankfully, students have taken to the streets and just like traditional grassroots activism, it’s all about being proactive, which includes getting off your comfortable chair and marching the streets to create change.

We’re setting a bad example for future generations with Kony 2012. While social media can be used effectively for certain causes (the Arab Spring protests is another example), it’s important to realize that it cannot be used for others. Coordination was the key for the Arab Spring and anti-SOPA campaigns, but it did not exist with Kony; there isn’t really anything else you can do besides click and share a link. You can’t congregate in a public place and share your discontent for Kony (unless you and your friends are willing to fly to Africa and look for him yourself).

This was the first real instance in our history where slacktivism was truly showcased. We need to reverse this dangerous trend and make sure that we deal with the next cause differently. With video production costs decreasing at an alarming rate, we need to educate people to show them the real potential social media has, as opposed to encouraging slacktivism and the habit of Facebook status-changing.

This is a new event for our generation: we’ve been thrust into uncharted waters, an environment where the barriers of participation have been lowered, and it’s suddenly become very easy to feel like we’re taking part in something big that will create change. We need to figure out when to pick our battles, so to speak.

In 2010, the Red Cross managed to raise more than $5 million in two days, via text message, following the Haiti earthquake. That happened largely because of social media and that’s a cause we have to support.

The Red Cross donations went to Haiti ― the Kony video will remain in cyberspace forever, while the man himself remains free somewhere in central Africa.

But at least you have a shiny new bracelet, right?