Pilot project would offer affordable student-reserved apartments

Moving in warm lamplight on a dusky late afternoon, CSU general coordinator Terry Wilkings stands with his arms extended, casting shadows on his office wall. His fingers become lines on invisible charts as his voice narrates the steady separation of his two hands. “The increase of cost year over year that students pay for housing far exceeds the rate of inflation,” he explains, his fingers arcing dramatically upwards.

It’s a trend that Wilkings claims has plagued the city for the past 30 years, and it’s a problem the Concordia Student Union (CSU) has decided to tackle—for better or for worse—with its ambitious cooperative student housing project. The goal is to create affordable, co-op student housing tied to the rate of inflation. The apartments are estimated to cost about $425-$450 a room per month and would be reserved for Concordia undergraduate students.

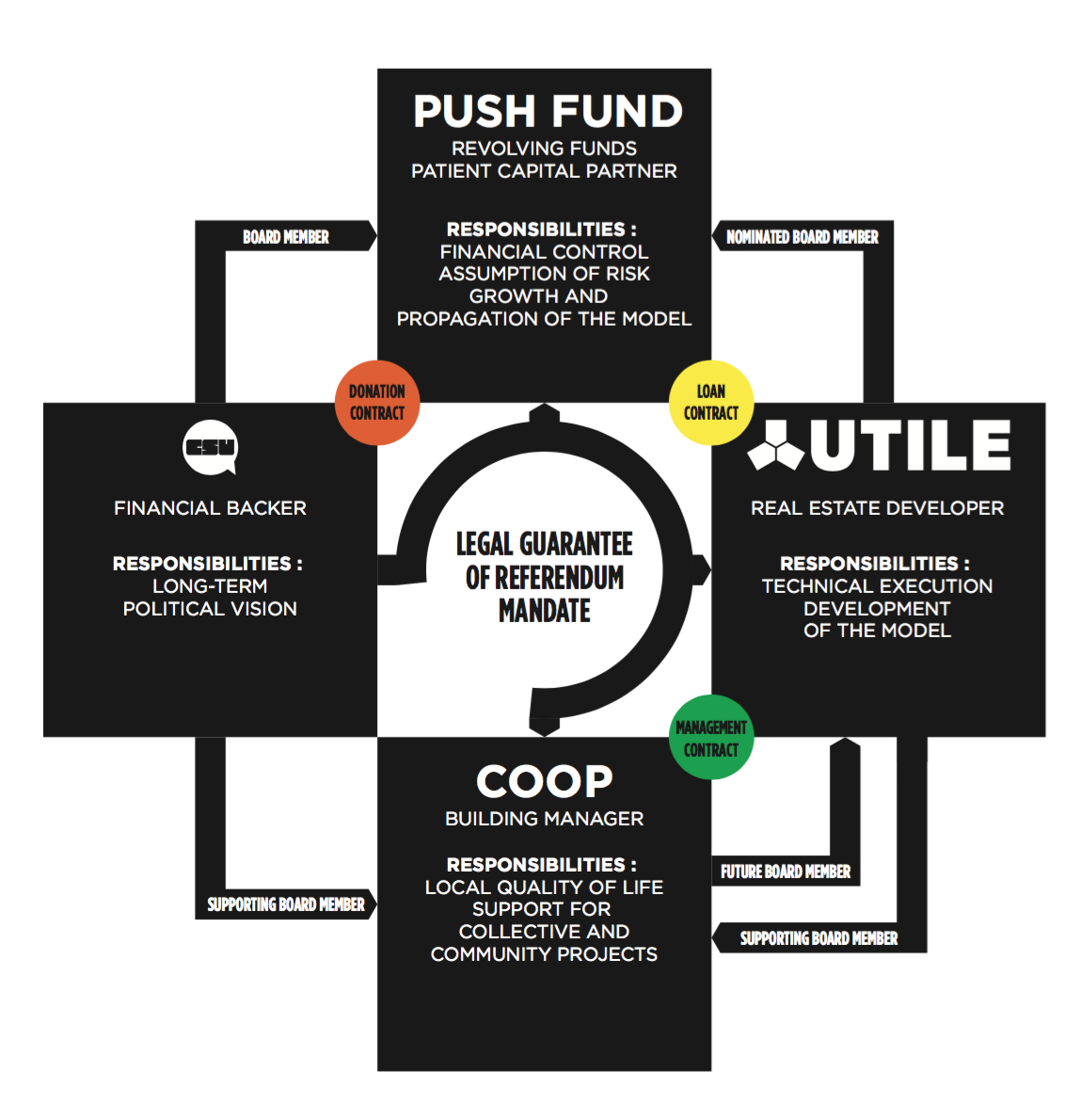

The project involves the CSU donating $1.85 million from the Student Space Accessible Education and Legal Contingency (SSAELC) fund into the new Popular University Student Housing (PUSH) fund. The donation accounts for approximately 15 per cent of the SSAELC’s total capital, and is a one-time donation from the CSU.

The PUSH fund will then contribute approximately 20 per cent of the total cost of the project, with the Chantier de l’économie sociale providing another 10 to 15 per cent. The remaining funds will come from a mortgage negotiated with Desjardins.

These funds would then be loaned to the non-profit group UTILE to acquire or build the exclusive student housing. Profits from the rent will be returned to the PUSH fund, so that the fund could one day take that capital and expand to create even more housing. The tenants of the co-op would be responsible for managing the property amongst themselves.

Wilkings said the acquisition of the property and the circumstances surrounding it are yet to be determined, but he expects the first students will be able to move in by 2019 at the latest. To start, the CSU is looking to ensure there are a minimum of 100 bedrooms available in at least one building. Currently, the priority will be in finding a location relatively close to the university, likely in an area such as St-Henri or N.D.G.

The project began in earnest in the summer of 2014, when the CSU participated in a study by UTILE that looked into affordable student housing in Montreal. The report concluded what many students in the city may already know.

“Students pay a lot more for housing than non-students,” said Wilkings. “It’s systematic. Students are unaware of their tenant rights, so they don’t exercise them. They face predatory landlords that literally prefer students because they don’t know their rights.”

It’s worse for international students, Wilkings said, though out-of-province students are close behind. On the whole, students pay over 30 per cent more than the median market rate. “We have a lot of out-of-province and international students,” said Wilkings. “[Concordia] has been disproportionately impacted by the private rental housing market in Montreal. After seeing the results of the survey … it would be irresponsible for us not to act.”

He claims that a lack of student housing is pushing students away from financially and socially responsible solutions.

“There are 800 residence beds at Concordia. We have 35,000 students,” said Wilkings. “We have several hundred-thousand students in Montreal, and there’s total—with all the residences—probably less than 10,000 [beds]. So where are these students going? They’re going to a predatory housing market.”

Wilkings cites for-profit student housing initiatives like EVO housing on Sherbrooke and near Bonaventure as ways students can be taken advantage of. “These private enterprises come in and charge well upwards of 50 per cent over the market median,” said Wilkings.

In addition to helping students, the CSU’s ultimate goal is to influence the municipal level to look into affordable student housing and to reverse the impact that students have on gentrification in the city.

“In [Coderre’s] platform … he was talking about how he wanted to bring families back into Montreal,” Wilkings said. “However, right now you have a scenario where a lot of apartments that would be for families are being occupied by two, three, four students sharing the rent cost. Four incomes can out-compete the one or two incomes of a family, and that’s how you’re seeing inflationary upward pressure on the housing market.”

Wilkings hopes that the co-op housing will help reverse that gentrification in the community by freeing those homes for families and residents. “We want to address the needs of students through housing, but also build collective solutions that can foster relationships between students, the university campus, and the neighbourhood community.”

The CSU coordinator hopes students will see the difference between the co-op housing project and student residences. “Personally, I find that residence living styles can be paternalistic,” Wilkings said. “There isn’t the same degree of independence.”

Students in the housing co-op will not be forced to comply with a meal plan, or any of the restrictions that come with living in residence. Essentially, the building will be an apartment building with affordable rent reserved for Concordia students.

Building student housing hasn’t been easy in the city. In 2005, UQAM attempted to create a new residence and commercial hub for its student population. The project, Îlot Voyageur, was canned only two years later after costs reportedly ballooned above $500 million. The Montreal Gazette reported that the project almost tumbled the university into bankruptcy, and student leaders cited Îlot Voyageur as an example of financial mismanagement.

“[Îlot Voyageur] was a big debacle,” Wilkings conceded. “As a result, there was a desire to address student housing. A recognition that student housing is problematic in this city.”

Wilkings hopes that once the student housing co-op is underway, they can explore further projects to benefit the neighbourhood. “We can develop collective projects for the community that have deep social impacts that far exceed the campus itself.”

In the future, Wilkings hopes once other student unions see that the project can succeed, that more of them will follow suit. “We’re empowering students to improve their own living conditions.”

For more information, visit the CSU’s website.