Part-time exercise science teacher John Boulay has worked at events like the Olympics and the Francophone Games

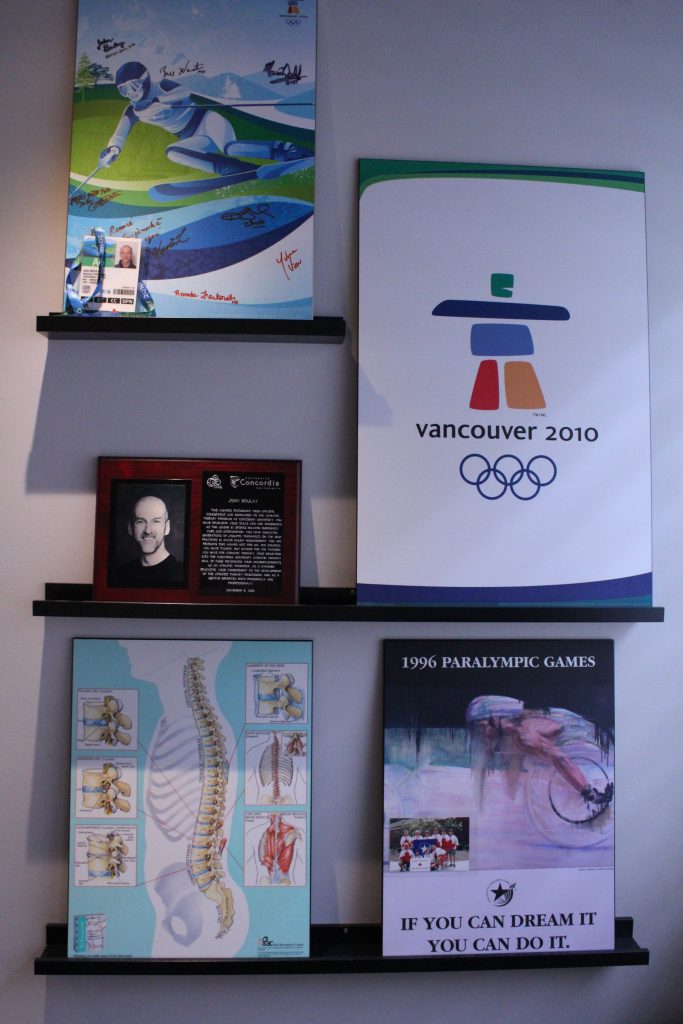

Just a few blocks away from Dawson College is the office of Concordia University part-time faculty professor John Boulay. Upon walking in, you are immediately greeted by a plastic spine in the corner of the room and the helmet of former Montreal Canadiens player Bob Gainey hanging on a coat rack by the door with a laser pointer attached to it.

The combination may be odd but it’s all part of his work. When Boulay isn’t teaching, he works as an osteopath and an athletic therapist at Osteo Med-Sport in Montreal, a clinic that specializes in injury rehabilitation and health maintenance.

Boulay said, while holding his Bob Gainey helmet with pride, that the helmet and the laser pointer are used on patients who are recovering from concussions. Essentially, the patient puts on the helmet and has to keep the laser pointer within a small circle. It’s a test to see if the patient is regaining their balance.

In terms of his teaching career, Boulay said he teaches what he knows. For the last 20 years, he has been a part-time exercise science teacher at Concordia, the same school he got his degree from.

“I was taking my classes at Loyola in the brand new exercise science program,” Boulay said. “Before I got there, the program was called biophysical education.”

Boulay knew he wanted to get into athletic therapy after injuring his knee in high school. He was a football player at the time and the athletic therapist for the team was one of his grade 10 classmates. Boulay said he thought his classmate’s skillset was interesting, and kept the profession in the back of his mind.

After graduating from Concordia, Boulay said there were only about two or three athletic therapists in the province at the time. This lack of therapists led Boulay and some friends he graduated with to open up their own clinic near the Olympic Stadium. However, as Boulay described it, politics and paperwork kept the clinic from opening.

Despite not opening the clinic at the stadium, Boulay was able to open one at Concordia, where he spent nearly a decade. The clinic at Concordia was called the Concordia University Sports Medicine Clinic and was open to the entire population of Montreal.

“We were asked to open the clinic but we were also asked to teach some undergraduate courses,” Boulay said. “We were just fresh out of our bachelors with no teaching degree. I was teaching kids the same age as me so I told them, ‘You don’t have to call me Mr. Boulay. You better call me John.’”

When Boulay and his partners opened the clinic, there were six national Olympic teams stationed in Montreal at the time, including the judo team, the wrestling team and the diving team. Since their clinic was the only clinic in Montreal, they became the go-to place for any national team athletes who were injured or needed care.

Of all of the teams, Boulay worked with the judo team the most and ended up working with them full-time for 22 years. During those 22 years, he was the Chair of the Sports Medicine and Science Committee for Judo Canada from 1985 to 2008.

“I went from provincial to national to international tournaments,” Boulay said. “I also went to the Olympics and the Pan Am Games. It was just a case of right place, right time and right opportunity.”

Boulay’s first experience with international competition was at the first-ever Francophone Games in Casablanca, Morocco in 1989. He explained that, at the time, the judo team’s budget was low, which meant he was the last line of defence if an athlete got injured.

“We were in the middle of the desert half the time,” Boulay said. “Honestly, it was quite rural and very backwards.”

After having gone to so many international competitions, Boulay said his favourite was by far the 2000 Olympic games in Sydney, Australia. He said he and his colleagues “had a ton of fun” over the 13 days, as they got to experience a new culture and exchange therapy techniques with trainers from other countries.

Boulay said the 2000 Olympics were also different from more recent ones because there wasn’t as much security present.

“It was a very innocent time,” Boulay said. “We’re talking about pre-9/11 so there was less security and everyone wanted to have fun and embrace the world. Everything was really open and friendly and we could visit the other mission houses.”

Aside from working with national teams, Boulay has collaborated with NHL and CFL teams. While he hasn’t treated the athletes directly, he has worked with the therapists who help rehabilitate the athletes.

“Usually, we get called in to consult when something bad happens,” Boulay said. “The first time I was called in to work with the NHL was when Richard Zednik of the Montreal Canadiens suffered a spinal injury. We’ve been helping the Montreal Canadiens’ guys for a few years now.”

Boulay’s career in athletic therapy led him to become the founding president of the Quebec Sports Medicine Council. He said his goal in creating the council was to bring athletic therapists together so that they could work as a team instead of as competition.

The council discusses ways to improve how athletic therapists perform their jobs. One issue they have all come together on is concussions and how to better treat athletes who suffer from them.

“Go back to the 1990s—concussions weren’t on anybody’s radar,” Boulay said. “[Athletic therapists] used to pull athletes out of competitions when they got concussions. The coaches would hate us, and it took three deaths for them to finally start listening to us.”

For the last 14 years, Boulay has been teaching the Advanced Emergency Care in Sport course, which teaches students how to react and take care of athletes who have sustained an injury.

He and one of his colleagues have collaborated on the course, with Boulay taking care of the theory aspect and his partner working on the more practical side of the course.

This year, however, Boulay found out he would not be teaching the course. According to Boulay, the exercise science program decided to take three courses from the curriculum and assign them to a teacher undergoing a limited-term appointment (LTA), which is a term that usually lasts three years.

“They decided to take a recent graduate who just finished their master’s and dumped our three courses on this poor person,” Boulay said. “I wish them well but it took me 13 years to figure out how to teach one course and I’ve been in the business 30 years. It’s a hard assignment.”

Boulay explained that, as a part-time faculty teacher, he realizes there are campus politics, especially when it comes to issues like LTAs. He said it can be frustrating when part-time faculty members have their courses taken away because by the time the replacement’s term has ended, the old teachers are off doing something else.

Despite losing his class this year, Boulay still teaches. However, he has to travel a bit farther as he now works at the Univsersité de Québec à Trois-Rivières (UQTR) and the Université de Sherbrooke. At UQTR, Boulay teaches two courses in their new exercise science program, and at Sherbrooke, he teaches sports care and first response.

Boulay said he’s able to balance his workload between Osteo-Med Sport and teaching because he has a passion for it.

“During the semester, I’ll take two mornings off of my clinic and actually lose money because my practice makes more money than teaching classes,” Boulay said. “But I do it because I love it. It’s not about money, it’s about giving back.”

He also added that what he teaches can help people in life or death situations which, for him, is important.

“Rule number one in my classes is that you’re going to encounter some deaths and my second rule is that you can’t change rule number one,” Boulay said. “Then there’s rule number three, which is that if we do our jobs right, we can lessen the amount of deaths we encounter and that’s really what it’s all about.”

Watch our extended video interview with John Boulay below.