Montreal researchers look at how the pill harms freshwater fish.

According to the Canadian Cancer Society, the 10,000 women who take contraceptive pills risk getting cancer one to two times in their lifetimes. For girls entering puberty, it has become the norm to use the contraceptive pill. Not only have studies shown that the pill can have harmful effects on the body, but it also impacts the environment.

“We found endocrine disruptors in the Saint Lawrence River,” said Daniel Cyr, in French, a professor in the Canada Research Chair in Reproductive Toxicology. “They come from an oestrogenic pill. People swallow a contraceptive pill, then they use the toilet. That waste water is then picked up and processed by water treatment plants. One part ends up back in the Saint Lawrence River, the other goes to a factory to become drinking water,” he explained.

Residue can be found in the river because estrogen goes through the filter. “We sent our study to the city and to the water treatment plant in 2002,” said Cyr. However, no changes have been implemented so far.

The major problem lies in what the pill is made of, and the consequences that follow once it’s been ingested. “This means that fish can gulp down the leftover residue. It causes their reproductive system to malfunction,” said Cyr.

Cyr and his team analyzed fish caught by fishermen in the Saint Lawrence River. “Eventually, male fish turn into female fish,” said Cyr. Knowing these results, researchers fed the fish to suckling rats. “These young male rats had lower spermatozoa counts due to the presence of this residue in the fat content of their breastfeeding mothers,” said Cyr.

These studies were completed between 2002 and 2004. Currently, the Institut national de la recherche scientifique’s (INRS) Institut Armand-Frappier, are not working on any other studies, due to a lack of contributors and funds. “There are still systematic studies,” said Cyr. “They found what we already found, but with other species and in other places. For example, they recently reported a high level of estrogen in fish. The same levels that are found in a girl going through puberty.”

On Oct. 19, The Concordian joined a group of environmental studies students visiting the Jean-R. Marcotte Wastewater Treatment Plant to learn about the process of cleaning water from Marc Girard, a former employee who now volunteers and leads tours of the plant. The amount of water the plant receives daily makes it the third biggest in the world, explained Girard.

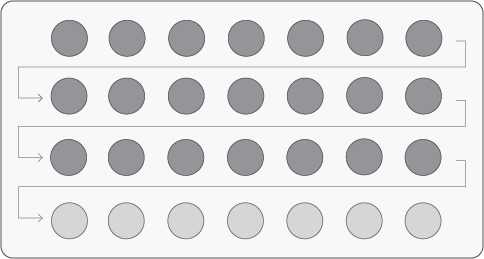

Before taking the students on a tour of the plant, Girard explained how polluted water is processed. “The product injected into the water forms flakes from the particles that are present in the water. This makes them heavier and they fall to the bottom of the tank, where they are later collected and incinerated,” said Girard. “With this system, we have 95 per cent clean water. Before, we used to put chlorine in the water to disinfect it at 100 per cent, but this damaged fauna and flora in the river. We found a solution with INRS to use ozonation (oxygen O3).” Ozonation not only eliminates pollutants from contraceptives, but from other pharmaceuticals as well.

The Jean-R. Marcotte plant is aware of the dangers of ecological imbalance. During the visit, Girard explained that three years ago, the plant launched a $400 million project. “We could be the first water treatment plant to use this technique. We are still looking for someone to pick up our construction bid,” added Girard. The project will be ready to use in three years.

The Concordian contacted the person in charge of the project, but they refused to comment.

One of the biggest rivers in the world continues to hold a lot of residue from contraceptive pills. According to Cyr, the impacts of contraceptive residue consumed by fish, which are then consumed by animals, could be similar for humans. As humans consume fish from the Saint Lawrence river, just like with rats, “the first signs may be lower counts of spermatozoa and malfunctioning reproductive systems in men.”

Graphic by Eleni Probonas.

Photo by Elise Martin.