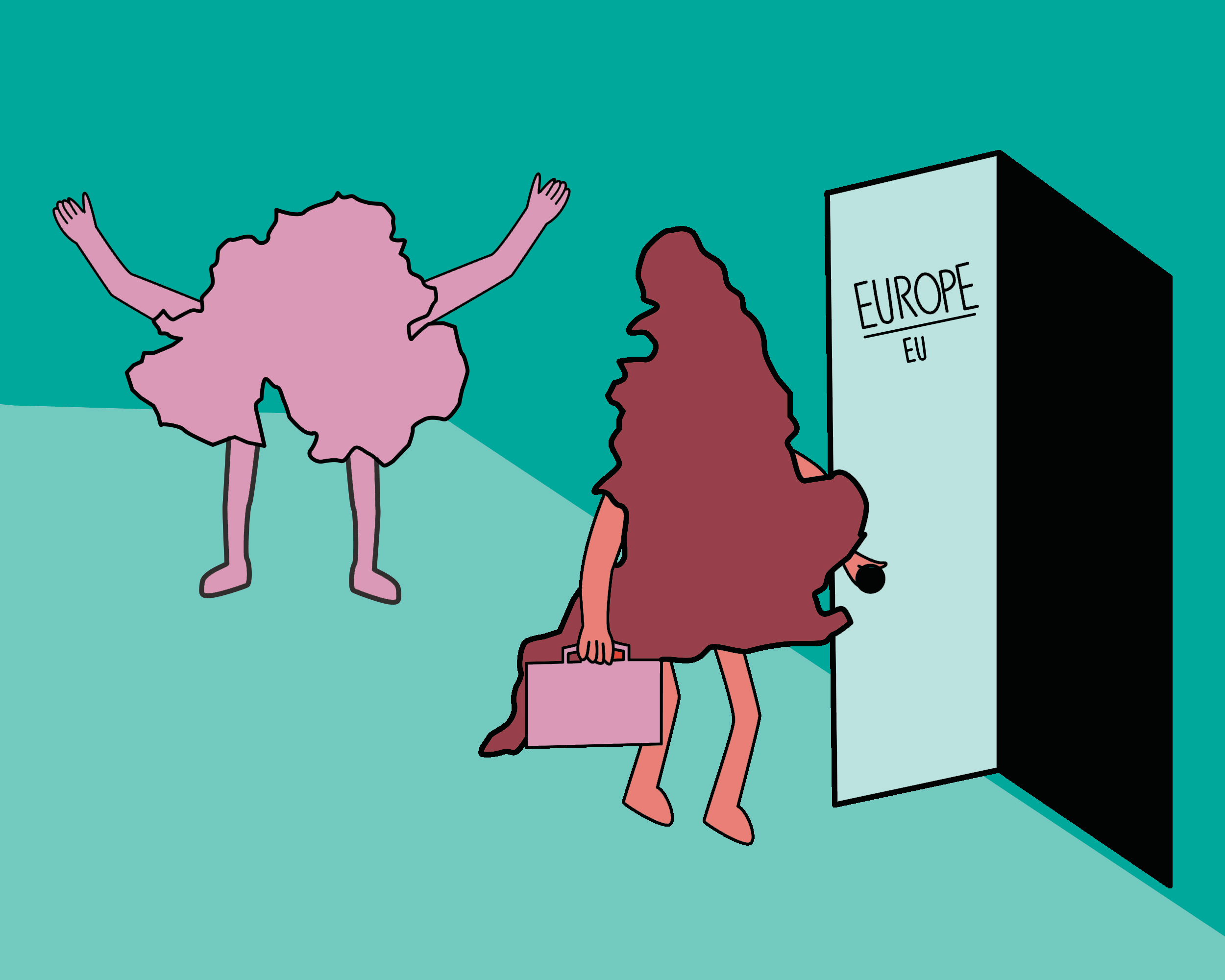

A Northern Ireland student’s take on Brexit and how it will affect his home

Within “Brexit”––the United Kingdom’s pending withdrawal from the European Union (EU)––is a lesson on how an international border can return to haunt the foreign power that imposed it, long before for reasons of political expediency.

The border that separates my native Northern Ireland (NI) from its southern neighbor, the Republic of Ireland (ROI), also separates Britain from an orderly Brexit which is ironic, since it was Britain that created the border when it partitioned Ireland in 1921. It would even be amusing if a disorderly Brexit wasn’t such a threat for Ireland, north and south.

In 2016, Brexit came about, largely, from British immigration angst. Since the NI-ROI border will be the UK’s only land border with the EU, you’d expect it to have customs posts, passport control, and barriers of some sort. However, this “hard border” scenario is problematic because of Ireland’s history and the tangled web of national identities that didn’t disappear with partition.

In NI, those citizens––usually Catholic––who identify as Irish see the border as an emotional reminder of partition that deprived them of basic civil liberties for 50 years. For instance, there were cases where access to social housing and to employment in private and public employment was denied to members of the Catholic community. However, some NI catholics pragmatically cherish the border for locking the UK into injecting roughly (CAN)$16 billion annually into the NI economy.

NI citizens––usually Protestant––who identify as British see the border as confirming the union with the UK and their own distinct society. Others, seeing their future in the EU, have obtained ROI (EU) passports and some might even buy into a united Ireland as to remain in the EU, according to The Irish Times.

Hardcore NI nationalists are fundamentally opposed to the border. In fact, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) would consider border infrastructures as “legitimate military targets.” But any border attacks by the IRA would provoke reprisals by the––mostly Protestant––Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF). In this way, a “hard” (visible) border might reignite the violence that ended with the 1998 Belfast Peace Agreement, according to The Washington Post.

Meanwhile, south of the border, ROI citizens see it as a firewall against the craziness of NI sectarian politics, which is why, in a 1999 referendum, they massively voted to relinquish the ROI’s constitutional claim of sovereignty over all of Ireland. However, the border question is not exclusively in their hands because the 1998 Belfast Peace Agreement allows NI’s Secretary of State to call a referendum on the status of the border. A similar referendum would have to be held in the ROI. How those referenda would play out is anyone’s guess.

To avoid a hard NI-ROI border, the UK’s Withdrawal Agreement includes a so called “backstop,” a post-Brexit temporary customs union between the UK and NI with the EU. However, after the UK’s attorney general judged that the backstop could tie the UK to the EU perhaps indefinitely, according to The Irish Times, the Withdrawal Agreement was struck down by more than 200 votes in the UK Parliament on Jan. 15, 2019.

At the end of January, Prime Minister Theresa May was considering an alternate backstop with technology replacing visible border infrastructures. If this option is rejected, the UK may crash out of the EU on March 29, creating a hard NI-ROI border and a possible return to armed conflict in NI, according to The Guardian.

Last year, I had a chilling reminder of the violence I knew growing up in Belfast. On DW’s “Belfast facing Brexit”, ex-IRA member Bob talks of bombers and ex-UVF member Noel, although referring to his past, speaks in the present tense: “I’ll shoot a Catholic nationalist … that way the message is sent to that community…” This is just one example of the consequences for NI, of Brexit, and the border.

Graphic by @spooky_soda