As I was reading the coverage of the recent Quebec Student Union (QSU) study, which found that 58 per cent of students in Quebec struggle with psychological distress, two things came to mind.

First, that this was not surprising in the least; since beginning my university studies, I’ve anecdotally heard and seen signs of stress, depression and burnout everywhere. Second, I couldn’t help but think that the recommended solutions do not address the root problem.

Among its recommendations, the QSU urged the provincial government to create a policy to improve the mental health of university students and to give schools money to offer psychological services.

Solutions that encourage “teaching students about mental health” put the responsibility on students to seek out these services. Yet there was little to no mention of the responsibility of universities to provide quality psychological services to their students. In reality, there is a clear problem with our university system.

If we want students to have improved mental health, we need to address the societal and institutional problems students are facing. We need to start questioning university as a structure.

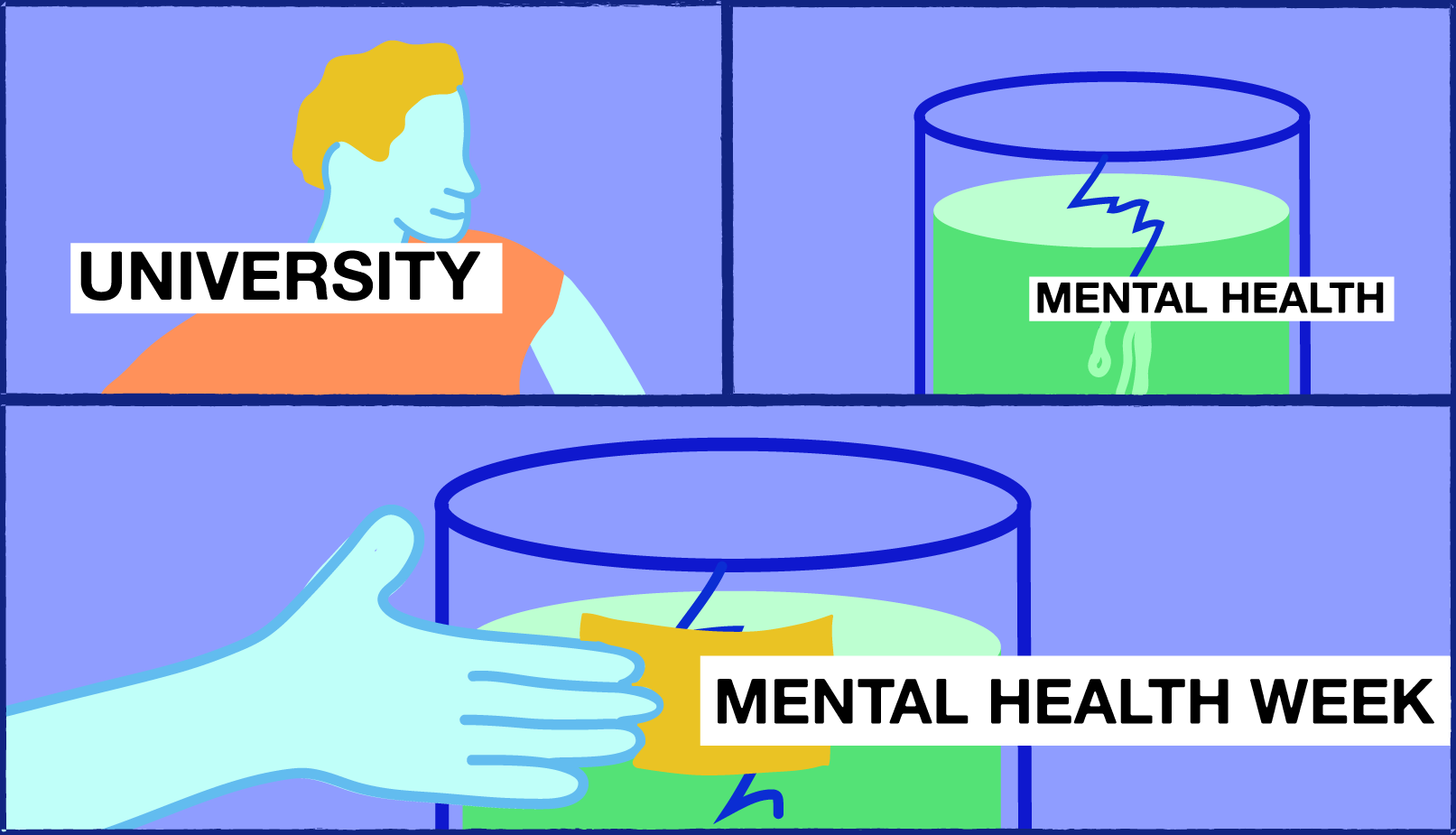

While having more psychological support resources on campus is great, it is important to note that these are merely band aid solutions. These resources cater to students who are already distressed. This is for when the damage has already been done and only help students deal with psychological issues after they’ve already been pushed too far.

Teaching students how to manage stress is important and necessary. Although it does not replace the need for a discussion surrounding the changing demands and pressures on students. Students’ daily lives and the expectations placed on students have changed drastically in the last few decades, and I question whether university structures have adapted to this changed reality as well. Nowadays most university students work, often full-time. This may be for financial reasons; many people cannot afford university without the extra cash. Some simply work to have spare change. But many students also work because of the changing employment situation. A university degree no longer guarantees a job after graduation.

In the current competitive job market, employers are often looking for previous work experience. Students feel the pressure to find relevant work experience not only during the summer break, but also while studying. The more some students gain work experience at university, the more other students feel the pressure to do the same in order to stand out when applying for jobs. It’s a vicious cycle. I’m not saying working while studying is a bad thing. On the contrary, it’s a great way to develop various skills you wouldn’t through university alone, make connections, enjoy financial independence and many more.

The problem is that universities have not adapted to this reality in the least. Instead, they operate on the assumption that school is the sole focus of students’ lives. They assume that we have the time and luxury to focus exclusively on our ever-growing pile of assignments and readings. From the moment the semester starts, students are on a speeding train they cannot keep up with. But we are told that this is what university is; that this is normal. So when we can’t keep up with the train, we feel attacked. It doesn’t have to be this way.

I’m thinking of the university system in Germany that I had the opportunity to experience last year while on an academic exchange. Most German university students also work while studying. The key difference is that the university system has adapted to this reality. Students have slightly less class time than here, but more importantly, they have less assignments throughout the semester. Most of the time, a course has either one final exam, or a final exam with an additional midterm exam. The final exams are scheduled a few weeks after the semester ends so students have time to study. Most of the time, if a student fails the final exam, there are opportunities to retake the exam without having to retake the class. This allows students to work during the semester without being overburdened with school assignments. Students can focus on studying more heavily once their classes are already over.

It’s also important to mention that a big portion of student jobs available in Germany aren’t minimum wage cashier or cafe jobs. Most companies and institutions have several “working student” jobs that offer valuable work experience and good pay. For someone studying economics, this could mean a student job at an NGO or at a consulting company. For someone studying communications, this could mean an a job at a PR or marketing agency while studying. From my experience, students in Germany experience a far better quality of life. They actually have a work-life balance, and have time to enjoy their friendships and focus on their interests outside of university. In Quebec, if you try to balance a social life, school work and actual work, you will quickly find you are no longer sleeping enough and your (mental) health is sharply declining.

If we want students to enjoy their university experience, we need to ensure that accommodations are made for their current lifestyles. Only a minority have the privilege not to work while studying in this day and age.

Graphic by @sundaeghost