The body positivity movement has seen a lot of change over the years. The question remains as to who are its rightful stakeholders

On March 21, 2015, celebrity event planner turned author and influencer Rachel Hollis made waves in the mom-blogosphere when she posted a photo of herself on a Cancun beach sporting her post-pregnancy stomach. In the photo, Hollis smiles, leaning forward, as her stomach forms small wrinkles on her otherwise small frame. In her caption, she writes, “My belly button is saggy… (which is something I didn’t even know was possible before!!) and I wear a bikini. I wear a bikini because I’m proud of this body and every mark on it. […] Flaunt that body with pride!”

Four rows down on her profile, in March of 2015, Hollis posted a photo of a cake celebrating her accomplishment of competing in the Los Angeles Marathon, writing “Thank goodness calories don’t count on marathon day!!”

So, you should flaunt your post-pregnancy body because you deserve to, but calories from cake should be a concern? Something’s not adding up.

This is not an attempt to single out Rachel Hollis (though she has had her fair share of controversies in the past). Her co-opting of body positivity in the service of a less-than-ideal relationship with food is part of a much larger trend.

Recently, there has been some high-profile backlash against the body positivity movement, with celebrities such as Lizzo suggesting that it has lost its focus on liberation. As the singer explains in an impassioned TikTok video, “Now that body positivity has been co-opted by all bodies, and people are finally celebrating medium and small girls and people who occasionally get rolls, fat people are still getting the short end of this movement.”

Indeed, what we now call “body positivity” grew out of the Fat Liberation movement of the late 1960s and 1970s. In those days, the aims of the movement were primarily to fight for the civil rights of fat individuals in healthcare and the workplace, as well as confronting the diet industry. This work continued through the decades and, as fat acceptance activist Stephanie Yeboah explained to Refinery29, in the late 2000s, the work moved online, as primarily fat, Black women shared their experiences with anti-fat bias and weight discrimination across social media groups and blogs. Around 2012, however, the movement exploded as people of all body types, including thinner creators, started claiming “body positivity.”

Now, on the one hand, this is a great thing. Arguably, any movement that helps normalize different body types and gets people talking candidly about their tumultuous relationships with their body image is a net positive for turning the tides of weight stigma.

As Dr. Sarah Nutter, Assistant Professor of counselling psychology and researcher of weight-related issues at the University of Victoria points out, weight stigma relies on what is called “healthy weight discourse.” This is the common conception that weight and health are inextricably linked, where a lower weight means a healthier body, and one can always achieve this through modifying their diet and/or lifestyle.

Dr. Nutter explained, “Inherent in ‘healthy weight discourse’ is this idea that weight is an individual and moral responsibility, and I think it’s that emotional aspect of morality that is really implicated in weight stigma and the way that people can respond to the body positivity movement.”

This notion is seen most strikingly in healthcare. Aubrey Gorden, a writer and podcaster who used to publish under the pseudonym “Your Fat Friend” until last year, discusses her experiences with medical weight stigma for Health Magazine. She explains that due to her size alone she does not receive the same quality of healthcare given to her skinnier friends. In the article, she describes the common occurrence of doctors not ordering necessary diagnostic tests, instead prescribing weight loss for any ailment under the sun (including, astonishingly, an ear infection).

Gorden writes, “I wondered how thin I would need to become in order to earn the kind of health care my thin friends got — a privilege that increasingly seemed reserved for those already perceived as healthy.”

Gorden believes, however, that despite good intentions, body positivity cannot solve this fundamental inequality deeply rooted in the healthcare system. She writes, “No matter how much we love our bodies, those of us living on the margins can’t love our way to good health.”

Though body positivity alone is never going to tear down the preconceptions keeping fat people ostracized, there is a real need for a movement that makes people in marginalized bodies (whether fat, queer, disabled, or otherwise) feel good about themselves in a world that wants them to be ashamed.

“To be able to curate a life […] that isn’t weight stigmatizing is really difficult,” explained Dr. Nutter. “For the health of everybody across the weight spectrum, getting rid of weight stigma is a really great idea.”

Zachary Fortier, a first year journalism and political science student, explained that while he finds a lot of issues with the current commodification of the body positive movement, there is still a necessity to promote fat acceptance.

“As a non-binary person assigned male at birth, my relationship with my body has been complicated,” explained Fortier. “Fatness and the celebration of bodies we’ve been told are ugly beyond repair is what fat acceptance is all about. Your body cannot be ‘beyond repair,’ what needs repairing is the jumble of harmful constructs that make up beauty.”

So, how can body positivity move to help uplift fat individuals, and not reproduce society’s focus on thinner bodies?

All sources point back to making sure body positivity retains its origins in fat liberation. While all people can feel bad in their bodies, it is important to acknowledge which bodies in society are the most marginalized, and fight the structures that keep them that way.

As Dr. Nutter explained, “Body positivity should be about accepting all bodies regardless of weight, size, or what bodies look like, and that all bodies have inherent worth and all bodies are beautiful. If that is truly the message, then that should be reflected in the [social media and publicized] imagery and whose voice is heard.”

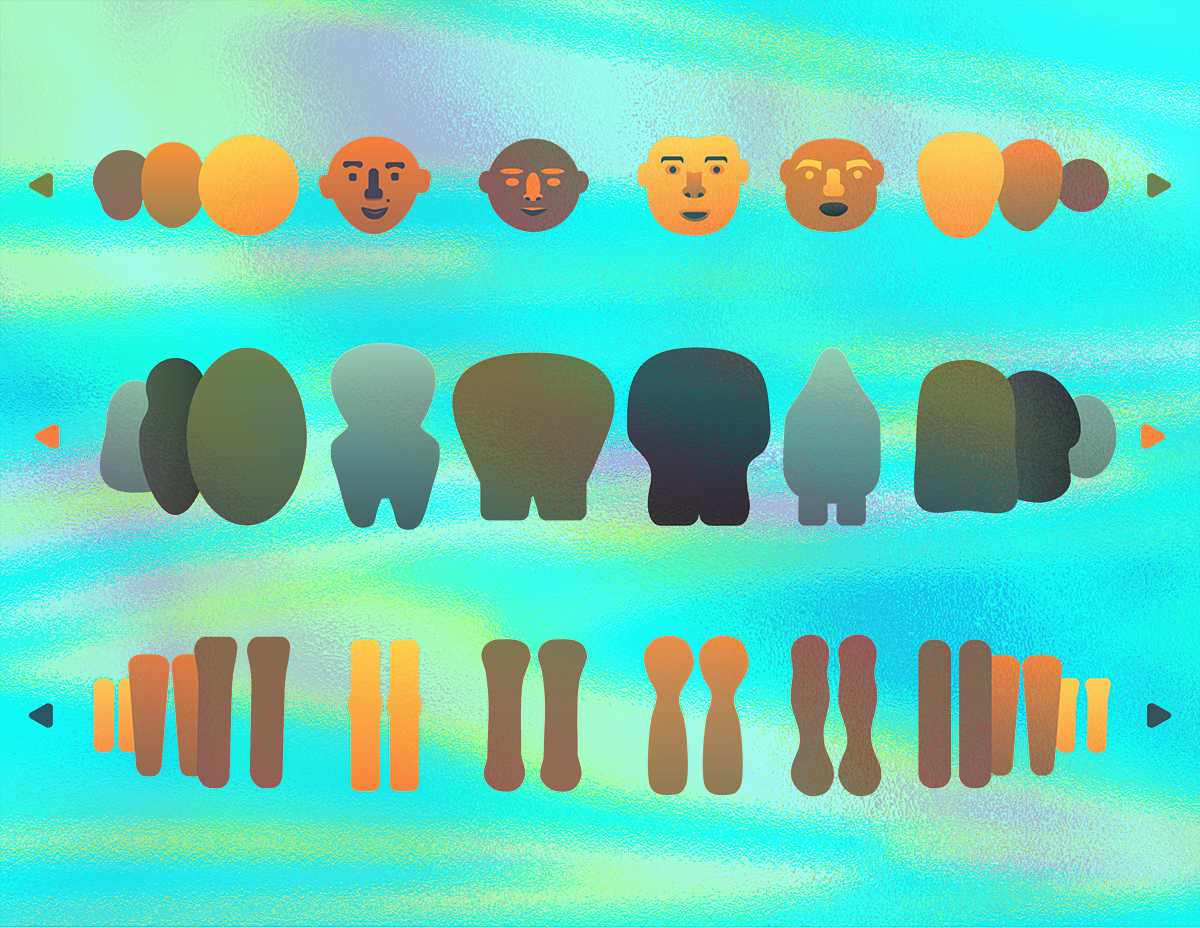

Graphic by Madeline Schmidt