Stop asking me where I’m really from because it’s none of your business

I was 10 years old when my parents told me to pack my suitcase and said, “We’re moving to Canada.”

As a kid, everything happened so fast, and I didn’t really understand where we were moving. Within a blink of an eye, I said goodbye to my friends, family, teachers, and left my home in Italy.

Growing up with my multicultural background in Montreal, I often got asked what culture I identified with the most.

That’s a hard question to answer. As a third culture kid (TCK), I’ve been unable to fully relate to any of the three cultures I grew up with: Italian, Filipino, and Canadian.

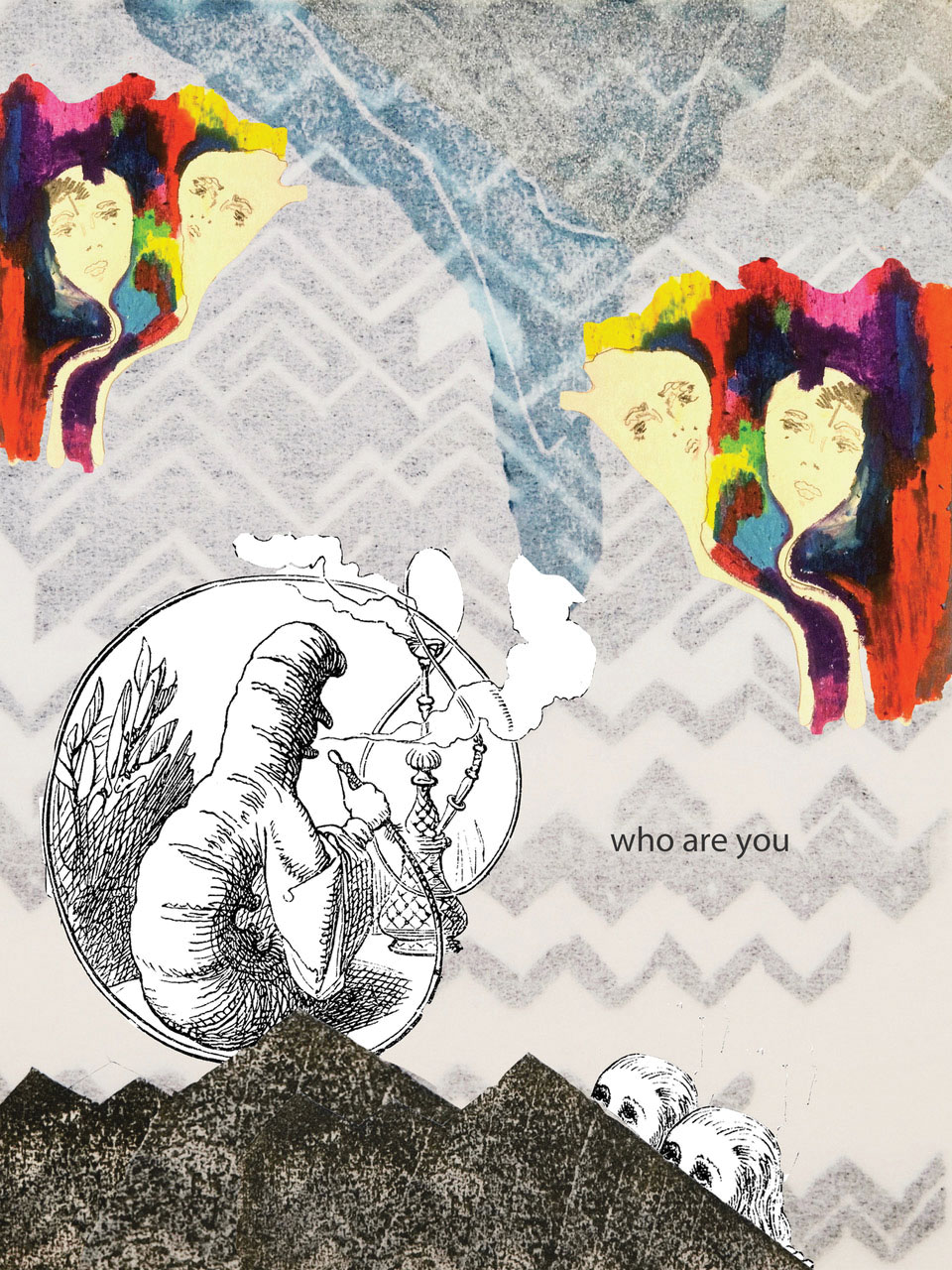

Who am I? Where do I belong? What defines my identity? These are questions that many TCKs ask themselves.

The TCK term was coined by an American sociologist Ruth Useem in the 1950s. A TCK is a child who grows up in a culture different from the one their parents grew up in. According to Merriam-Webster, “The ‘third culture’ to which the term refers is the mixed identity that a child assumes, influenced both by their parents’ culture and the culture in which they are raised.”

When I moved to Montreal, I was amazed by the multiculturalism. It was refreshing to see so many different cultures existing side-by-side. However, I was shocked to find out how unwelcoming some people in the city were at times, despite the melting pot of cultures around them. Though, I didn’t understand at that time.

One of my first encounters with racism was in my elementary school here in Montreal. I vividly remember my classmates asking me where I was really from. Initially, I didn’t understand what they meant.

Until I heard them say, “Well, you look Asian, how come you’re Italian?” Ouch, I thought. Why would they ask me such a thing?

To me, it was normal. So, I explained. My parents are originally from the Philippines, but they moved to Italy, met in Rome and lived in Italy for more than 20 years. The kids insisted that I wasn’t Italian because I didn’t have citizenship.

They didn’t know that those born in Italy are not automatically citizens unless a parent is an Italian citizen. However, those who are born in Italy to foreign parents can become Italian at 18.

In my case, my parents did not want to give up their Filipino citizenship to get the Italian one. I was born and raised in Italy, but I’m not a citizen, because I left at the age of 10.

After a few years of living in Montreal, I realized that every time someone asked me where I was really from, it was a microaggression. Their question implied that I couldn’t be from Italy because I’m not white.

Why was it so hard for people to understand and accept that I considered myself Italian because of the culture I grew up in?

The first language I learned was Italian. Not once did I conversate in Tagalog (the spoken language in the Philippines), nor did I grow up eating Filipino food. It felt strange to identify as a Filipino because I had never associated with its culture.

Within my first year in Montreal, I had to curate the perfect answer for this question to avoid further probing and undesired comments.

This was only the beginning of my identity crisis.

Why did I let friends and strangers define my identity? Why couldn’t I consider myself Italian regardless of what my papers said? It was easier to let others label me and define my identity to fit their expectations without constantly explaining myself.

Whenever I identified myself as an Italian, I had to explain my whole life story and always got mixed reactions. This was uncomfortable.

As the years went by, I let myself assimilate to Quebec culture. I learned how to speak French and English. I mastered the perfect Montreal accent just to fit in.

I abandoned my Italian culture and gave up on telling people that I considered myself Italian.

Forgetting I was born in Italy and spent my childhood there was a small price to pay if it meant I could finally fit in somewhere.

Today, I rarely get asked where I’m from, partially because I no longer have a thick Italian accent when speaking in English and try to avoid the conversation before it can even begin.

This summer, I had the opportunity of going back to Italy after 11 years of being in Montreal. I got to see my family and my childhood friends. We visited my old house and my old neighbours.

As a 10-year-old, relocation to another country didn’t affect me. When I finally revisited my old home for the first time since we left, I was able to reconnect with my Italian “roots” that I had abandoned. I was reminded of my childhood in Italy and the life I had before moving to Montreal.

It was easier to block out my childhood memories in Italy and pretend that I had always lived in Canada in order to fit in.

After returning from my trip to Italy, I finally processed all the emotions that I couldn’t feel as a child. I grieved the life I lost and the citizenship I could have had if I stayed eight more years. I cried for my 10-year-old self, who packed up her life, left her friends and relatives, and flew across the world only to lose her culture and identity.

I now understand what it means to be a TCK, and I accept all my cultures as part of my identity. As a TCK, it’s impossible for me to identify with one culture without raising questions. I’m Italian, Filipino and Canadian, regardless of what my papers say. My citizenship doesn’t define my identity.

Feature graphic by Maio