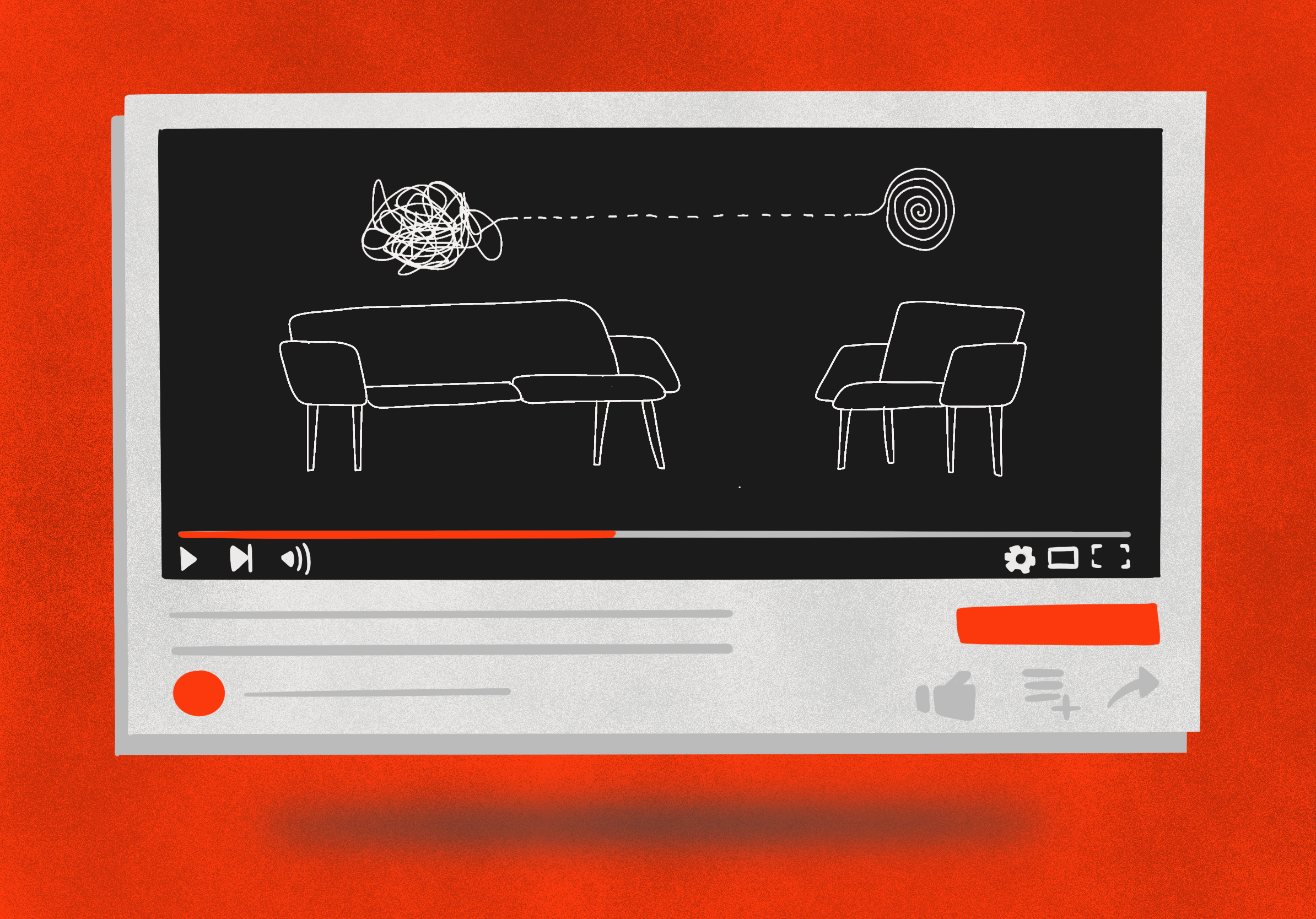

Is the solution to mental wellness finally here, or is it just another fad?

In the 1980s, a psychological theory became all the rage in North America and started to be implemented in institutions across Canada and the United States. You might be familiar with it; it’s now known as the self-esteem movement.

It was based on The Psychology of Self-Esteem, a book originally published in 1969 by Nathaniel Branden, which essentially explains that the key to happiness and success is to work on building a positive self-image for everyone. As the literature on this topic grew, it caught the attention of Californian legislator John Vasconcellos, who loved the idea so much he started funding initiatives to make it a greater part of his state’s policies.

All of a sudden, schools were giving out participation medals by the handfuls and finding ways to compliment children no matter what. Educators found all sorts of ways of minimizing the concepts of “winner” and “loser” in the activities they organized.

And this went on into the 90s. Today, we know that that was complete nonsense; you can’t tell a kid they’re special and coddle them and expect them to continue breaking down barriers and outdoing themselves in everything they undertake. One day they will step into reality and realize that if everyone is unique, then that means no one is.

This is exactly what has happened as a result of this movement. We now have a generation of people who are struggling with mental health issues and broken expectations because they’ve been conditioned to life in a bubble and now have to live in a world that won’t be telling them they’re amazing and great all the time.

In turn, this has caused a societal fear of making mistakes and a culture that favours dishonesty over the possibility of hurting someone’s feelings.

But, at the time, this clearly seemed like a great idea. Everyone agreed: low self-esteem causes people to take less risks, to isolate themselves, to turn in subpar quality work because they don’t believe they can do better, and in general just kind of sucks.

On the other hand, high self-esteem gives many people a drive to become better, to chase their dreams;… the bottom line is, people who view themselves highly invite others to do the same.

The thing they forgot to mention in this movement, however, is that people need a reason to esteem themselves highly. Phenomenal self-perception paired with a terrible personality and a lack of competence is narcissism at best, and will set anyone up for failure.

The more we learn about psychology, the more we realize how little we know about the human brain. In 1973, psychologist David Rosenhan conducted a study where he sent fake patients to 12 psychiatric hospitals in the United States and told the admitting doctors they heard voices in their heads saying the words “empty,” “hollow,” and “thud” — but apart from that, they told the truth about everything else, including that none of them had a history of mental illness.

They were all admitted to psychiatric hospitals for up to almost eight weeks and all prescribed various medications.

Full disclosure, journalist Susannah Cahalan somewhat debunked this study in 2019. She found many inconsistencies in the story and suspects some of the pseudopatients were made up by Rosenhan.

But nonetheless, the moral of this study remains and has been retested many times thereafter: even highly trained doctors have trouble telling the difference between people who are mentally ill and those who aren’t.

Psychology gets inserted into popular culture all the time. In the 2010s, self-esteem was replaced by its distant cousins, self-care and self-help; by 2017, the global wellness industry was worth US$4.2 trillion.

And now, these ideas of ‘change your life by changing your mindset,’ ‘98 per cent of what you do is caused by your habits,’ and ‘you can do anything you set your mind to’ are seeing a huge surge. The new psychology trend is telling you to take control over your own life because no one’s going to do it for you.

So far, implementing these rules into my life has brought me nothing but positive results and psychological progress. But frankly, I don’t know if this could work for everyone. I don’t know if it’s realistic to tell people that they are responsible for their own success and failure, especially when we start factoring in things like systemic discrimination and wealth inequality around the world.

Could this be the next self-esteem movement? We don’t want to teach people that they can’t do anything and that they won’t be able to achieve their big dreams? Then again, there could be consequences to getting carried away by yet another idealistic method of fixing all of our problems and finally finding happiness.

Graphic by @the.beta.lab