With the introduction of a commission-free delivery app, restaurants are given a lifeline

It is no secret that the restaurant and food industry is suffering from some effects of the pandemic.

The average restaurant in normal times could attribute most of their business to dine-in service, with take-out and delivery sales making up a smaller portion of revenues. Nowadays with in-house dining not being an option, all of Quebec restaurants’ revenues are from the takeout and delivery avenues.

While provinces like Ontario and British Columbia have set caps on the commission fees that delivery services like SkipTheDishes and UberEats can charge to restaurants, the Quebec government has all but done the same.

Though some of these services have offset the initial costs to set up their use for restaurants, the large commission fees are weighing down the open restaurants, and have brought others to close their doors.

Sherif Hafez, owner of Essence restaurant in downtown Montreal, has closed his restaurant after trying to operate with delivery services like SkipTheDishes for six months, saying, “You’re basically working for them and there’s nothing left for yourself.”

When the costs of operation such as labour, hydro and rent are put into the equation, and on top of that delivery services skim 30 to 35 per cent, “It wasn’t worth it at all to operate,” said Hafez.

Quebec restaurants that have thrived off the merit and business of the customer that dines in, are sinking. According to business owners like Hafez, the government is turning its back on them.

“I think it’s along the lines of the lack of support to the industry. The provincial government has not been supportive of the industry at all,” he said.

In light of these needs for restaurants, a new commission-free delivery service has arisen: CHK PLZ. To date, the app has received an average of a 4.7/5 user rating between the iOS and Google Play app stores.

The app does not take such high percentages off the top of restaurants’ orders, but rather a fixed rate per transaction. Instead of having its own fleet of drivers, the company partners with rideshare services, such as Montreal-based company, Eva.

When asked if he would consider trying out a commission free delivery service, Hafez said he would be open to trying the idea out.

Annie Clavette, owner of Le Gras Dur and Maamm Bolduc in Montreal, has enjoyed her experience with the service thus far.

“We like [CHK PLZ] very much but the sad part is not enough customers use it; UberEats is the more expensive and the most popular one — go figure,” she said.

While Le Gras Dur is available for order on a variety of delivery platforms, Clavette’s approach has seen her relocate the setup as a ghost kitchen at Maamm Bolduc. The ghost kitchen model sees restaurants geared towards takeout and delivery specifically — it is essentially just an operating kitchen, without having the added space of a dining room and a bar. By doing so, restaurants are able to save on many operational costs, much like a food truck.

Though Clavette has worked hard to receive support from the Association Restauration Québec, no new regulations or support systems have trickled down the grapevine as of yet.

For business owners like Clavette and Hafez, having to fight for support from the government to keep your profits can be demoralizing.

As Clavette put it, “It is very frustrating, you feel you are begging for your money.”

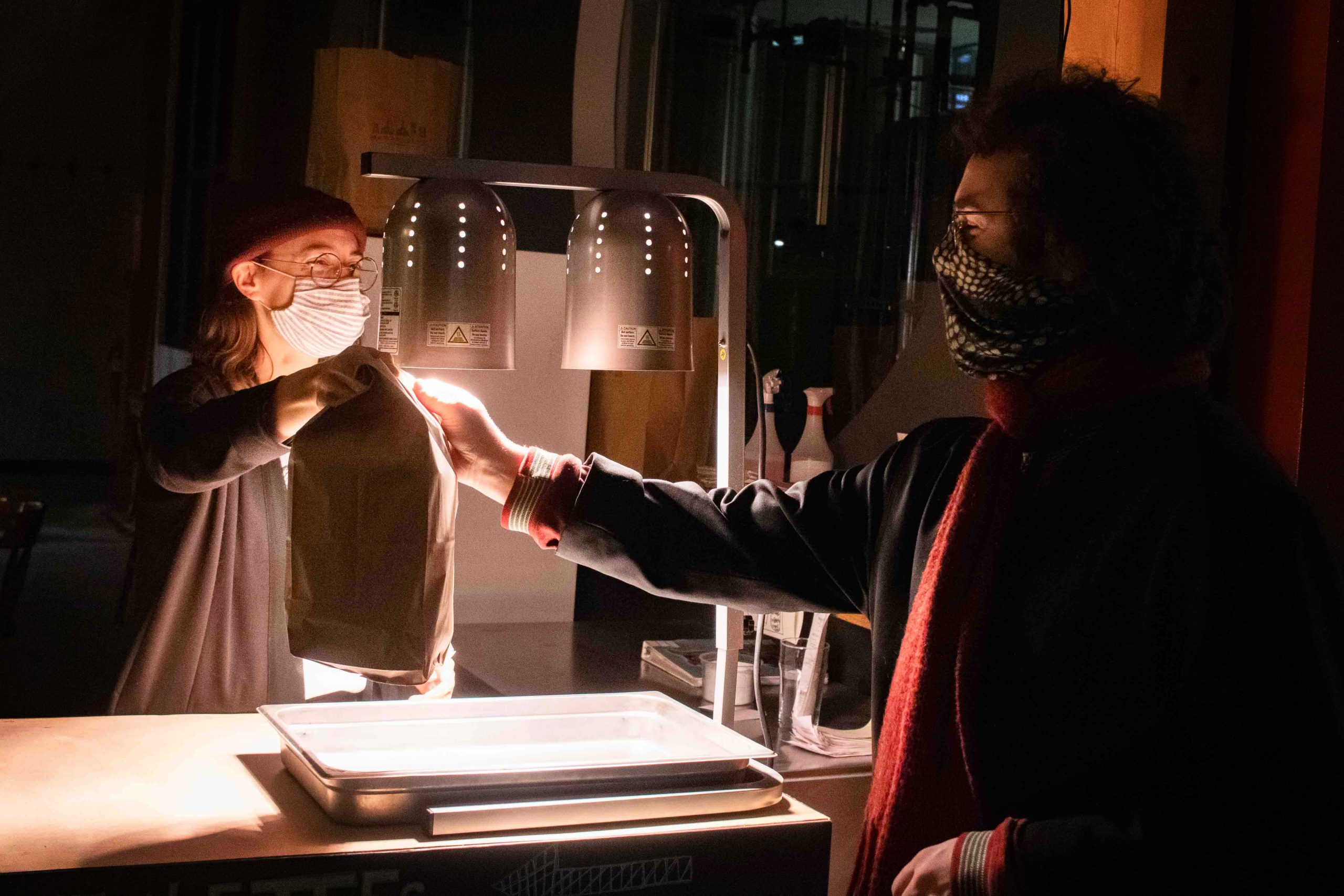

Photograph by Christine Beaudoin