Filmmakers explore the great soundtracks that accompanied their films’ classic scenes

“One thing about commercial films is, doesn’t the music almost always really suck. I mean isn’t it always the same shit?” – Jim Jarmusch, MovieMaker Magazine, 2004.

The importance of the use of music in cinema cannot be overemphasized, with the exception that sometimes the artistic intent of a film relies on silence. That being said, with the overuse of clichéd songs in films today, such as “Escape (the Pina Colada Song)” by Rupert Holmes, we look to the past to explore filmmakers who understood how to effectively pair their artistic visions with brilliantly paired music.

The famous American filmmaker Mike Nichols passed away only a week ago on Nov. 19. It seems only appropriate and necessary to discuss what is arguably his most famous film, The Graduate. Anyone who has seen this 1967 film will remember how Nichols cleverly complemented the angst-ridden, coming of age story with the sounds of folk duo Simon and Garfunkel.

According to Peter Fornatale’s book, Simon & Garfunkel’s Bookends, choosing the music of Simon and Garfunkel was an idea that came to Nichols in the shower—as all brilliant ideas usually do. While many of the songs used in the film had been released before the film was even made, the final song, “Mrs. Robinson,” was only a skeleton. Once Nichols had decided to collaborate with Art Garfunkel and Paul Simon, “Mrs. Robinson” was aptly titled and a few more verses were written.

The final version used in the film was still a simpler version of the one released on Bookends in 1968. Watching The Graduate takes the viewer back in time aesthetically, but also aurally, as the distinct sounds of Simon and Garfunkel are associated with the turbulent times in America during the 1960s.

In keeping with Nichols’ tradition, Jarmusch has worked with music icons such as Neil Young and Tom Waits to commission the music that accompanies his films. Jarmusch has frequently emphasized the importance of music and film, suggesting the two artistic processes are quite similar.

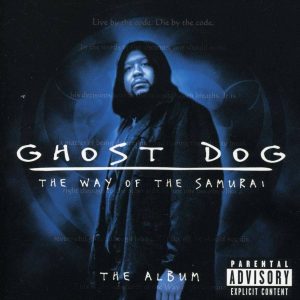

Notably, Jarmusch worked with hip-hop musician and producer, RZA, of Wu-Tang Clan, to compose material for Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (1999).

RZA was hired to do the score and would allegedly disappear, watch the rushes, record material, then bring it to the studio for Jarmusch to experiment with. Unlike the material recorded for Jarmusch’s Dead Man (1995) wherein Neil Young would play and record as the film was playing and the music would remain chronologically intact, Jarmusch was able to play with RZA’s score and cut up tracks or layer them together.

In a Q&A video on YouTube from Marcelo Paulo De Souza, Jarmusch ultimately explained that neither musician composed with the intent to manipulate viewers into feeling specific emotions. He said “[Young and RZA] really wanted to make something that grew out of their impressions of the film [and add] another layer of texture.”

The fitting tracks composed for Jarmusch’s films further demonstrate the originality of the work, and whether they are used diegetically or not, the music and sounds contribute to the overall atmosphere and world in which the films exist.

Alternatively, Stanley Kubrick and Terrence Malick are two incredibly influential directors who hired composers for their films. Later, they chose instead to use classical material that had been written decades or even centuries before. Kubrick had planned to use the talents of composer Alex North to create the sounds for 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Amazingly Kubrick’s decision to use older compositions from composers such as Johann Strauss and Aram Khachaturian worked to his advantage.

Scenes from 2001 matched with Strauss’ “Blue Danube Waltz,” for example, turned into legendary spectacles of film history. Kubrick once suggested in an interview with Michael Ciment that “however good our best film composers may be, they are not aBeethoven, a Mozart or a Brahms. Why use music which is less good when there is such a multitude of great orchestral music available from the past and from our own time?”

This notion was confirmed when Terrence Malick commissioned well-known contemporary composer Alexandre Desplat to create the accompaniment to Malick’s The Tree of Life (2011), but instead used already existing classical tracks. For Malick, the choice was a rewarding one. The beauty of the film is owed, in part, to the exquisite tracks from composers such as John Tavener and Henryk Górecki. By pairing the equally talented musicians’ work with the filmmaker’s vision, these movies were catapulted into the memorable vault of classics for generations.