Last week’s article looked at hip-hop’s beginnings, and we now dive into the genre’s corporate soul

(A continuation from last week’s piece on the issue)

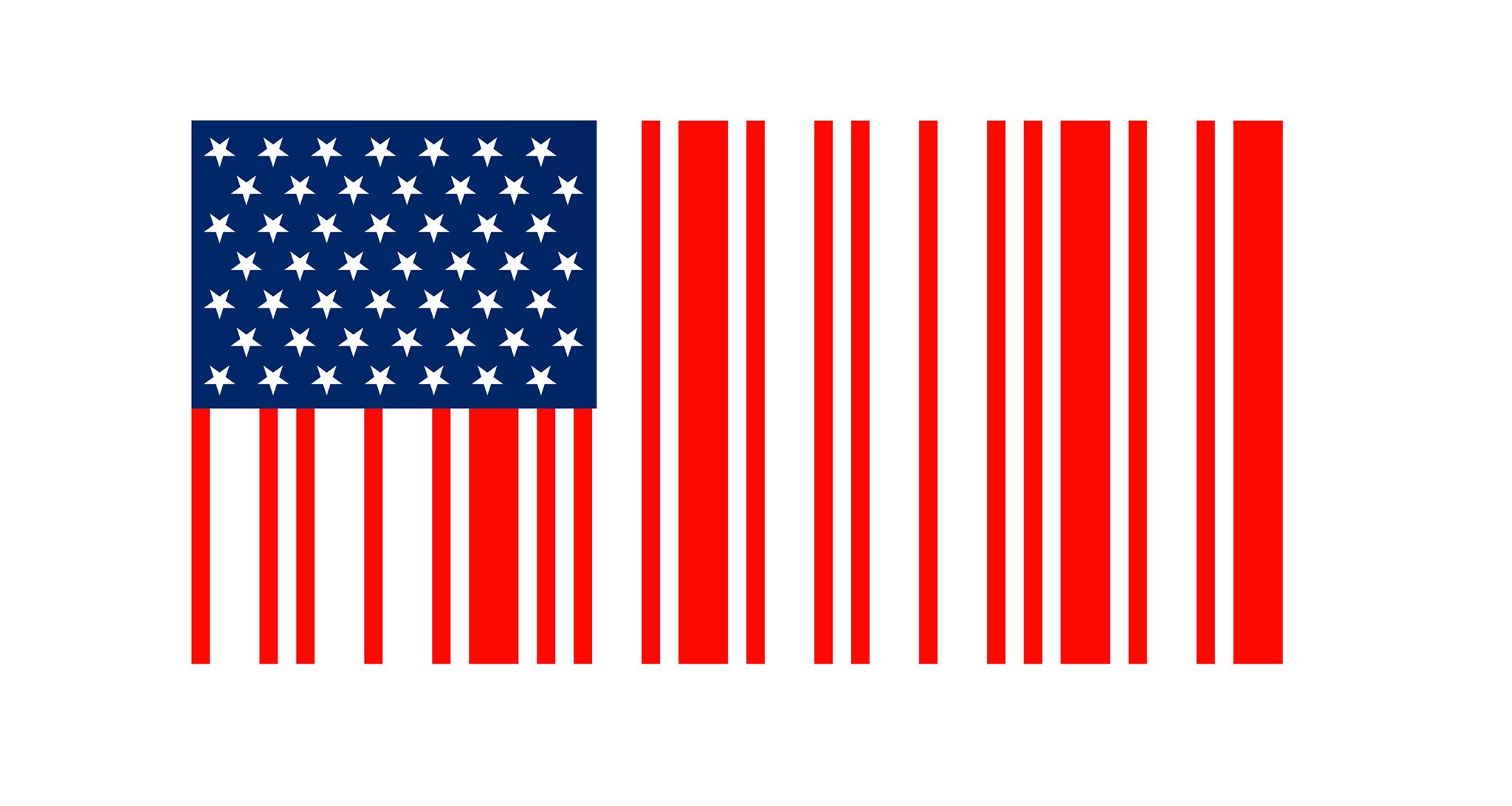

Call me skeptical, but anybody who thinks that the interests of black America will take priority over the interests of corporate America probably has a very optimistic understanding of capitalism. Although some puritans will debate the exact moment corporate America decided, “Hey! We can package and sell this!” hip-hop’s commercialization arguably began in 1986; the first year rap albums started appearing on the Billboards. From then onwards, hip-hop was to be considered as much of a commodity as it was an art form, a class of brandable merchandise whose primary goal was to capture market share by delivering consistent quality and digestible programming.

Unsurprisingly, the music’s capacity to provide insightful cultural commentary took a backseat role. Rap musicians were now contributing to somebody’s bottom line, and maybe if they felt like it, also chose to paint that all-too familiar image of the black American experience in their music. Whatever the case, the profitability of specific musicians and topics would dictate who or what was to be pushed to the majority. Here we are in 2015, and whether or not those same practices remain detrimental to hip-hop culture—and by extension, the black community— has become largely irrelevant. If the financial interests of the music industry were dependent on an artist’s profitability, why change a recipe that has been so historically bankable? For hip-hop to be lucrative in the United States, it must remain familiar to the 63 per cent of people who compose the majority of its population: white America.

The thing is, white America has been listening to hip-hop music for quite a while, now. That is hardly news to anybody. Hip-Hop: Beyond Beats & Rhymes, a documentary directed by Byron Hurt, stated it plainly: white people consume 70 per cent of “all hip-hop produced” (the exact implications of that remain unclear), they have also been making hip-hop music for quite a while, and with great success. The Beastie Boys’ License to Ill became the first hip-hop album to hit the Billboards in 1986. But as we have come to understand, hip-hop music’s original source of inspiration were the laments of the disadvantaged, frustrated and marginalized; the realities that blacks faced in the United States, which was, if we can be blunt, historically the consequence of white people. Macklemore, probably one of the most controversial white people in music right now, provided very germane perspective during his interview on Hot 97, where he affirmed that as a culture that came “from pain, that came from white oppression,” he will not “disregard… [his] place in [hip-hop] as a white [person.]” Indeed, some very constructive dialogue at such a fragile period for race relations in hip-hop culture, and in America.

I’ll take a hot minute to drop a quick PSA for you, humble reader: this is not an article calling for the banishment of white people from hip-hop. White people have been contributing positively to the culture for decades. On top of that, it would be downright insulting towards pretty much every race to equate all of white America with corporate America. Maybe 2014 being the music industry’s most unprofitable year to date (according to Forbes) is just a symptom of how truly out of touch the industry has become with hip-hop culture. Let the eruption of online discussion revolving around Macklemore’s victory over Kendrick Lamar at the 2014 Grammys act as substantial proof of that disconnect. There have undoubtedly been upsets at the Grammys before, but what made this upset particularly remarkable is realizing how people were more agitated by the transparency of the decision-making process than anything else; today, the Grammys are more comparable to a showroom than an art gallery. It serves as nothing more than a presentation of the music industry’s “most popular products,” in much the same way that the Billboards do. Corporate America is focused on delivering prepackaged hip-hop content that caters to a national audience, where two out of three people are Caucasian. So no wonder that we are seeing less and less black hip-hop artists receiving accolades.

I guess we have come to realize that the influence exercised by corporate America over hip-hop is beginning to jeopardize the legitimacy of the genre as an art form. The unfortunate reality of the situation is that when art becomes product, the narrative of its creation is rarely dictated by what the artist thinks you need as a viewer. Instead, it is dictated by what the industry thinks you want as a customer. Neither the people, nor the sounds of hip-hop continue to serve its modus operandi. People are struggling with the definition of hip-hop because the industry’s presentation and acknowledgement of what truly constitutes hip-hop can no longer be fully corroborated by the black experience in America. It is for this reason alone, that hip-hop is in danger.