A year after the album’s release, the world still hasn’t quite recovered

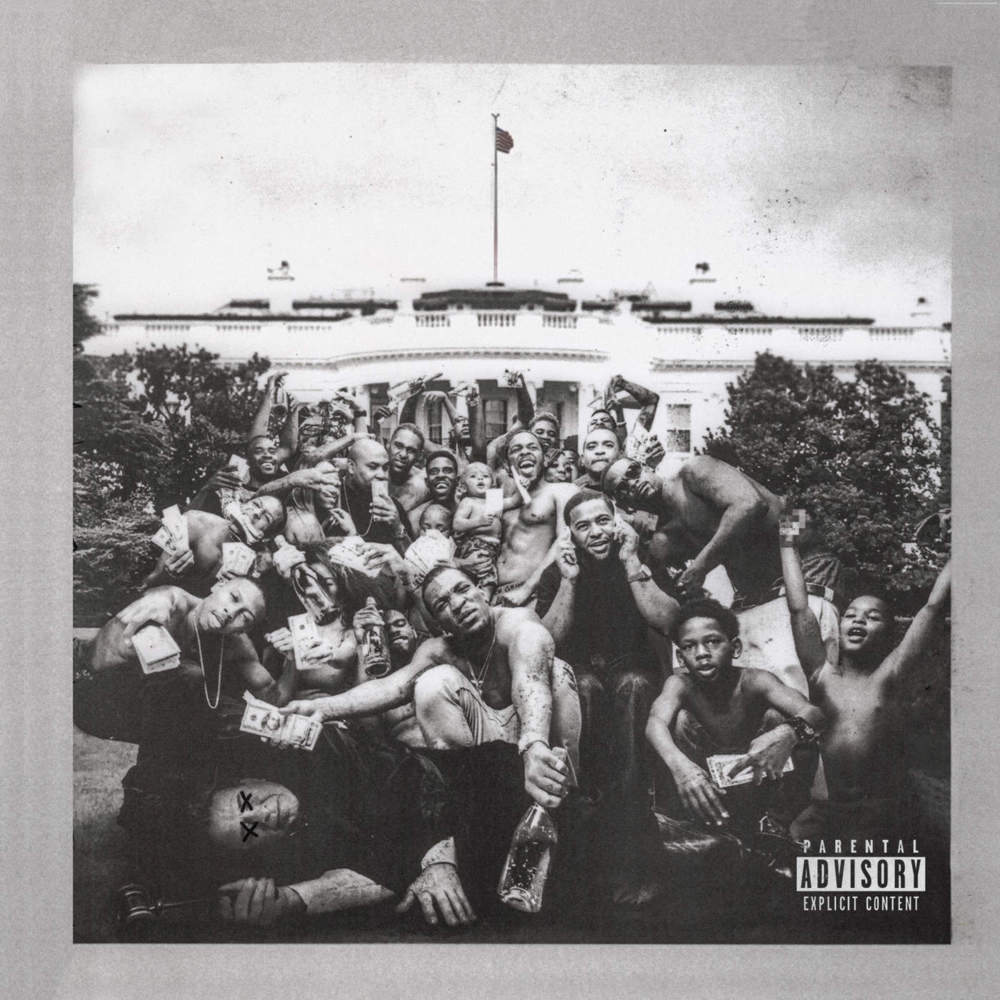

With Section.80, we were formally introduced to Compton’s Kendrick Lamar. With good kid, m.A.A.d. City, we fell in love with the rapper, his densely layered and autobiographical narrative transporting us to a stark, dangerous and very real world. Even with these increasingly staggering releases, nothing really prepared us for To Pimp a Butterfly.

With four universally lauded releases under his belt, his latest in the form of a compilation released on March 4, Kendrick Lamar is fast becoming one of hip-hop’s most important songwriters and one of contemporary music’s standout artists. In the year since To Pimp a Butterfly was released, the dialogue surrounding the album has barely waned. If anything, its impact and reverence has only grown with time, influencing genre contemporaries and giving people, namely black Americans, a sliver of genuine hope in the face of continued oppression.

So why is To Pimp a Butterfly so highly regarded and what sets it apart from genre contemporaries like, say, Kanye West or Run the Jewels’ latest? For one, its scope is simply astounding; at 78 minutes and 16 tracks, the album explores deeply personal thematic content with unparalleled precision. Exploring the concept of black celebrity within a uniformly white system in a selfless, deeply intimate manner, Lamar touches on everything from racial inequality, toxic materialism and institutionalized discrimination while positing the entire experience through his own personal lens. Chronicling his ascent into stardom and personal descent into depression, Lamar focuses on identity and what it means to be a black man in modern America. In doing so, Lamar brings his audience to eerily unsettling corners of the human psyche, as in the heart-breaking “u” — perhaps one of the most vivid depictions of depression ever portrayed in music.

Most impressively, Lamar accomplishes the most personal and sermonizing of dialogues without ever sacrificing the album’s accomplished musicality. Featuring jazzy instrumentals by Thundercat and Kamasi Washington and the production work of Flying Lotus, Boy-1da and Pharrell Williams among many others, To Pimp a Butterfly exhibits a rich, textured and incredibly organic sonic palette that’s at once lavish and equally tasteful in light of its thematic content. As Lamar bares his soul, gorgeous string arrangements flutter while a host of jazzy horns blare freely.

As a result, Lamar’s vision is wholly uncompromised, with no selections feeling like perfunctory radio hits. With an album as critically and commercially successful as good kid, m.A.A.d. City comes creative carte blanche, and the rapper puts this to exemplary use.

Given Kendrick Lamar’s stature as a hip-hop heavyweight, one could argue his influence on the medium’s public face is undeniable, with many acts attempting to follow in his footsteps. After all, To Pimp a Butterfly’s raucous single “The Blacker the Berry” inspired nuanced debate in regards to its closing twist detailing its central hypocrisy. In the face of mounting frustration in the United States with regards to the unfair treatment of blacks, Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly got the ball rolling in a big way, inspiring mainstream contemporaries to tackle these issues head-on in an effort to add to the conversation, for better or worse.

Take Macklemore’s “White Privilege II” for example, a song with good intentions and an interesting alternative point of view on the matter that’s ultimately undone by its lack of musicality and hokey, unfocused content. Though Macklemore is no stranger to social issues, his attempts at tackling the Black Lives Matter protests in a nuanced way come up incredibly short; at over eight minutes in length, the song is simply too drawn out for radio appeal and too narratively scattershot to serve as a statement. In the end, it’s a song with a valid point of view and discourse that’s ultimately for no one. If Lamar influenced a wave of social activism in hip-hop, the level at which he accomplishes this is made resoundingly clear simply by looking at some of his contemporaries.

Most importantly however, it’s impossible to ignore To Pimp a Butterfly’s massive cultural impact. In its attempts to discuss systemic racism and the flaws of black and white America, the album found a very passionate audience among black Americans. It swiftly became the soundtrack to a struggling black America, instilling a sense of hope and empowerment in the face of mounting police violence and criminal negligence against blacks. Protesters nationwide took to the streets chanting the chorus to “Alright,” an agitated declaration of hope in the face of pain and strife, in an effort to send a vivid message. In an article for Rolling Stone, writer Greg Tate likened “Alright” as the “We Shall Overcome” of our generation. He also attributes both To Pimp a Butterfly and D’Angelo’s long-awaited Black Messiah as “the first tuneful meditations of this era to come within spitting distance of canonical conscious-groove masterworks like Curtis Mayfeild’s Superfly and Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On.”

Ultimately, 2015 was an interesting year for hip-hop and black music, with the genre being acknowledged by many as the voice of a struggling generation. Take Run the Jewels’ Killer Mike for example; a year ago, the mainstream struggled to put a face to his name, yet here he is making the rounds as Bernie Sanders’ very own hype man. Though there’s still a long way to go, artists like Kendrick Lamar and D’Angelo have provoked fruitful and interesting conversations on difficult topics, contextualizing much of black America’s problems without ever simplifying them. Though Taylor Swift’s 2014 album 1989 was deemed 2016’s Album of the Year by the Grammy Awards, To Pimp a Butterfly’s continued impact not only on music but on social movements across America ultimately renders this declaration inert.