Canada’s Ukrainian diaspora is working to remove Russian influence from their culture amid the ongoing conflict.

It’s been a while since Mariia Zaborovska has spoken Russian, her mother tongue. She, her husband, and their two children all conversed in the language regularly at their home in Montreal, even seven years after immigrating to Canada from Ukraine. Following Russia’s invasion of eastern Ukraine in the winter of 2022, she switched to Ukrainian—a show of solidarity for her compatriots, and a small but significant effort to eliminate Russia’s cultural influence on the eastern European nation.

Zaborovska is not alone in her decision, nor is language the only change taking place. The Russo-Ukrainian war has sparked a greater movement among Canada’s Ukrainian diaspora to draw a line between Russian and Ukrainian identity and culture. This comes after numerous historical periods of Russian territorial occupation, and repeated efforts by Russia to stomp out all traces of Ukrainian identity and culture—an imperialist endeavour that has bled into the 21st century.

The war has created a ‘cultural emergence’ in many Ukrainian diaspora communities across the country, according to Milana Nikolko, an adjunct research professor at the Institute of European, Russian and Eurasian Studies at Carleton University.

She explained how in the past, there would often be disputes among the Ukrainian diaspora over how Russia’s actions against their home country could be perceived. “We do have a significant shift in terms of not just how we describe the war, but also what language we use in our everyday communication,” Nikolko said.

Nikolko is part of a group of Ukrainian expats who communicated among themselves in Russian prior to 2022, switching to Ukrainian after the war began.“Even though it may not be so efficient, we are putting our effort into making Ukrainian the language of communication between us,” she said.

Adopting the language

Transitioning to Ukrainian was not an easy venture for Zaborovska. She grew up in Crimea, a heavily Russian-speaking peninsula which had been part of Ukraine until Russian annexation in 2014, and had little knowledge of the Ukrainian language. Russian music, blogs, literature and YouTube videos were eschewed from her everyday routine in favour of Ukrainian-language content.

Zaborovska started off by practising Ukrainian at home. “My husband and kids carried on for a while in Russian,” she said. “And then my husband also switched to Ukrainian. And then very quickly, in the matter of a few weeks, we noticed that the kids were speaking Ukrainian.”

She was amazed by their progress, even more so when her elder daughter, aged 6, asked her mother what their first language was. “Well, unfortunately it’s Russian,” Zaborovska said with a laugh. “And she was so surprised, like she didn’t recall speaking Russian […] It was amazing how far they kind of switched.”

Eventually, Zaborovska started speaking Ukrainian outside of her home. In doing so, she developed a closer connection with Montreal’s Ukrainian community.

Unity in nationhood

Zaborovska views these changes in language and lifestyle, as a small victory for Ukraine against the claims made by the Russian government and president that Ukrainians and Russians are the same people.

Hanna Kovalenko, a Ukrainian refugee and former resident of Mariupol, vehemently disagrees with those claims. Mariupol was one of the first cities invaded by the Russian army in February 2022—Kovalenko and her family escaped, arriving in Montreal the following May.

“We have a national culture [that’s] different from Russia,” she said. “I speak Russian and other people speak Russian in Mariupol. There was no discrimination!”

Polina Khrystuk, a political science student at Concordia University and Ukrainian immigrant, agrees. “As someone who grew up in eastern Ukraine, I know what language was actually oppressed, and it wasn’t Russian,” she explained. “It wasn’t socially cool to use Ukrainian . . . it didn’t have the strong social status the Russian language had.”

Having immigrated to Canada with her family 14 years ago, Khrystuk said it was interesting to see the love local Ukrainian communities had for their country and culture. “There’s a big joke going on in Ukraine that the best people who speak Ukrainian are the Canadian Ukrainians, because they’re the ones who try to preserve the culture the most,” she added.

A history of Russian oppression

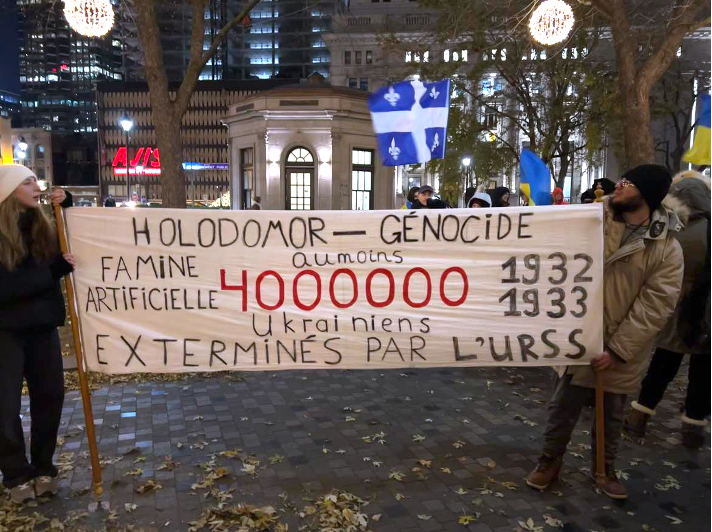

Zaborovska, Nikolko, Kovalenko, Khrystuk and many other Ukrainians in Canada are well versed in the history of Russian oppression of the Ukrainian language and culture. One such historic instance looms large in the collective memory of Ukrainians: the Holodomor. Literally translated as “death by starvation,” the Holodomor was a famine orchestrated by the Soviet Union which killed some four million Ukrainians from 1932-1933.

Starving Ukrainians sold family heirlooms for meagre portions of grain. Some were forced to resort to cannibalism. All international relief efforts were blocked by the Soviet government. Thirty-five countries recognize the Holodomor as a genocide, including Canada, the United States and most countries in the European Union.

Nikolko draws distinct parallels between the Holodomor and the current Russo-Ukrainian war. Both tragedies involved Russian aggression against the smaller Ukraine, and both triggered an “emotional symbolic unity” of Ukrainians around the world. “We have the same story told in a different way,” she said.

The destruction of Ukrainian infrastructure last winter by the Russian Armed Forces left many in eastern Ukraine facing the bitter cold without power. This led to the term “Kholodomor” (literally death by cold) being coined by historian Alexander J. Motyl to describe Russia’s brutal disregard for the lives of Ukrainian civilians.

Daring to speak out

The Holodomor was not just designed to kill Ukrainians, Zaborosvka explained: “It’s meant to instill this fear [for] generations to come […] It is so deeply instilled that it is a taboo. It is a topic you’re not supposed to speak about.”

She believes that’s why it’s important that modern-day Ukrainians speak out about it, and about other atrocities Ukrainians have suffered and continue to suffer at the hands of Russia.

Since the war began, Zaborovska helped organize numerous rallies, protests, and other events designed to show support for Ukraine and keep Canadians from turning a blind eye to the war.

Zaboroska said that becoming a social activist was not a conscious decision, but was rather something she felt needed to be done to show support for her home country from thousands of kilometres away.

Zaborovska’s activist group also organizes events highlighting past injustices. For example, a Holodomor Memorial Day vigil and rally took place at Place Dorchester in downtown Montreal on Saturday, Nov. 25, 2023.

Over a hundred supporters braved the -8 ºC weather, bundled up with winter wear. Blue and yellow bicolour flags filled the square, flying alongside several Quebec and Canadian flags. The group marched for over an hour that evening. Their chant rang out:

“Holodomor is genocide. Let’s not forget those who died.”

Events like these mourn the millions of victims of the genocide. They also demonstrate to the Russian government that they no longer have a stranglehold on Ukrainians’ spirit, Zaborovska explained.

A permanent change

Zaborovska’s ancestors spoke Ukrainian, but her grandparents had made the switch to Russian and had passed the language down to their children.

“It was frowned upon in the Soviet Union to speak Ukrainian,” she explained. “If you wanted to advance in your career, you had to be a Russian speaker […] In that sense, I’m coming back to Ukrainian culture, coming back to [the] Ukrainian language.”

She does not plan on reverting back to Russian after the war ends, regardless of the outcome. “[Russian] feels so strange and foreign to me now […] When I come back to the videos of our family archive and I hear myself speak Russian, it feels, to be honest, like a different person speaking. And I’m not so sure I like that person.”

“The language you speak definitely makes a lot of internal difference in you,” she added, “I’m definitely not going back to Russian.”