Around 30 per cent of Concordia’s Indigenous students are out-of-province. How will the tuition hikes affect the community?

During recent strikes, student advocates have brought to light the effect tuition hikes may have on Concordia’s student services, as the university loses out-of-province students and the income generated from their tuition. Indigenous faculty and staff fear a potential cut in the services offered to Indigenous students.

“We believe that these tuition hikes are catastrophic,” said Manon Tremblay, Senior Director of the Office of Indigenous Directions (OID) and Plains Cree from Muskeg Lake Cree Nation. “And not just from an institutional budget standpoint. They’re catastrophic in terms of our ability to offer students a unique experience.”

While Concordia does not have specific data about Indigenous students, the OID estimates that about 30 per cent of them are out-of-province.

“If we don’t get those numbers of students, then we’re going to have a small population,” said Allan Vicaire, Senior Advisor of the Office of Indigenous Directions and Mi’kmaq from Listuguj, Quebec. “It doesn’t enrich the campus and the community at Otsenhákta [Student Center]. I worry about that. I worry about the future of Indigenous education within Quebec.”

According to Vicaire, this diversity in students and experiences is crucial in the effort to decolonize Concordia and other anglophone universities in Quebec.

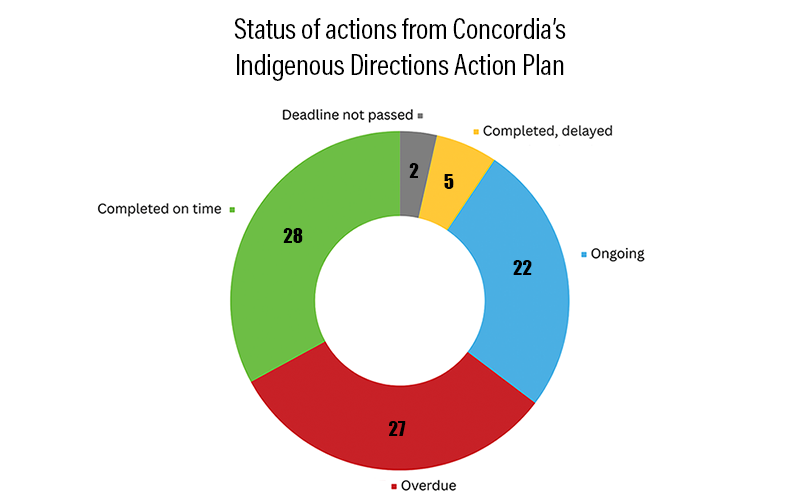

“We’re attracting all these wonderful Indigenous youth, First Nations, Inuit and Métis youth, and that’s why this is able to progress,” he said. “So when we have those students coming out-of-province, they’re bringing a richness and pushing the agenda for the Indigenous Directions Action Plan.”

Tremblay fears the hikes will encourage Indigenous students to stay in their own province or study in other provinces instead. The announcement of the tuition hikes came right after universities in Ontario, including University of Toronto and University of Waterloo, announced that they will offer free tuition to Indigenous students from communities around their campuses, and in-province tuition rates for Indigenous students throughout Canada.

Catherine Richardson Kineweskwêw, director of the First Peoples Studies program and member of the Métis Nation of British Columbia with Cree and Gwichʼin ancestry, said the language requirements accompanying the tuition hikes will create additional barriers for Indigenous students.

“Why don’t we forefront Indigenous languages?” she said. “Quebec had two layers of colonization [French and English]. Whenever you impose a colonial European language, it’s always Indigenous people that suffer.”

Tremblay believes Indigenous students will not appreciate this obligation to learn French during their time at university.

“Asking them to learn another colonial language, that’s not going to go down very well,” she said. “We are in a situation of catastrophic language loss for our own languages. Obviously people will counter by saying that if I have to put my back into learning another language, it’s going to be my own ancestral language, not another colonial one.”

The OID is working on scholarship offerings for out-of-province Indigenous students, but they still have little information in terms of what a post-tuition hike budget will look like.

“The picture is still very unclear,” Tremblay said. “There’s going to be cuts, that’s obvious, and I think everybody knows that. Where those cuts are going to be, I don’t know.”

For Cheyenne Henry, manager of the Otsenhákta Student Centre and Anishinaabe from Roseau River First Nation, it is important that the university continues to focus on decolonization.

“With the changes that are forthcoming, tuition increases and the potential reduction of out-of-province students to the institution, those are big things that are on the table now,” she said. “But despite that, there still needs to be the commitment to Indigenous students and indigenizing these spaces.”