The Green Party of Quebec is looking to make catcalling a ticketable offence

At 9 a.m. on a winter morning, Sarah Shaw left her apartment wearing a long coat and scarf—neither of which revealed her skin or figure. She walked down the street, and as a group of four men passed by, they began making remarks.

“Hey sexy,” one of them said. Shaw ignored him, but the tallest of the men tried to corner her against a wall. She managed to walk away, but the same man called back to her: “You stupid bitch, you think you’re so much better than me. You don’t even have an ass anyway.”

“I remember it so clearly, because it was so horrifying,” said Shaw, a fine arts student at Concordia. “Men think you owe them attention.”

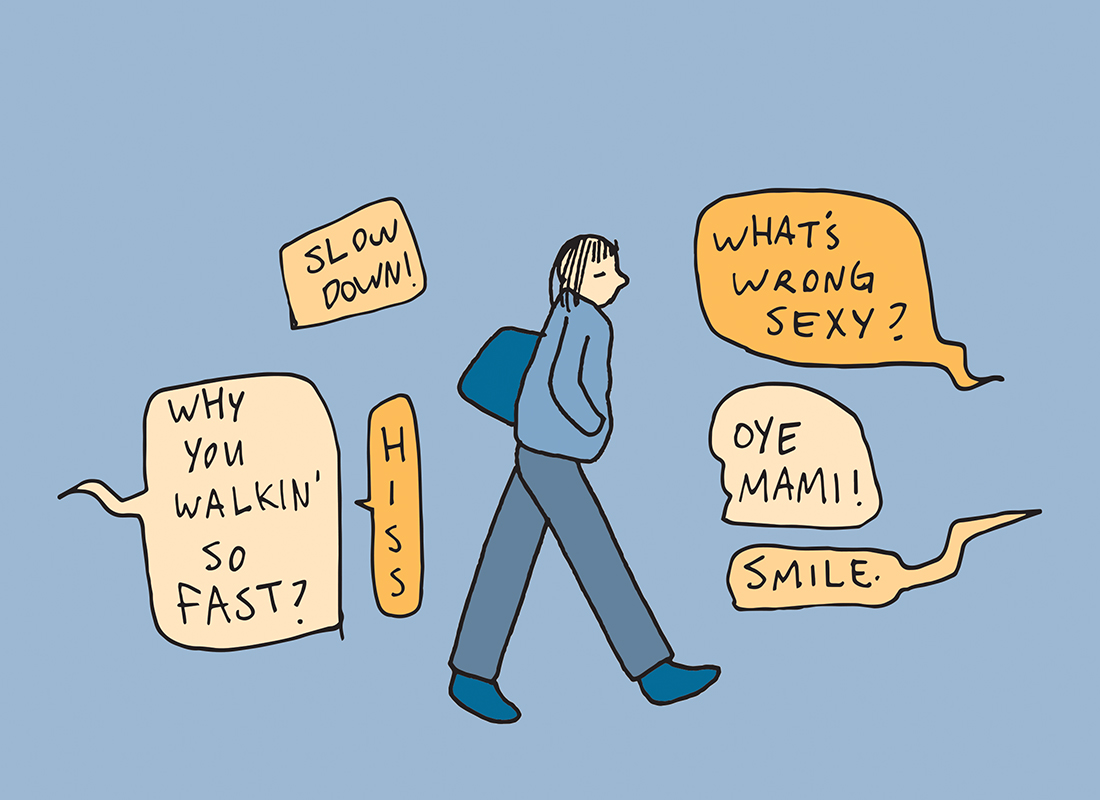

Like many people who identify women, Shaw is accustomed to this type of commentary known as “catcalling.” It usually involves yelling sexual or derogatory comments at women in a public setting. Based on her experiences, Shaw said this behaviour is prevalent both in Montreal and her small suburban hometown in the United States.

“I just listen to music,” she said. “Part of it is for me, so I don’t have to hear [the catcalling]—but also so I don’t have to deal with it.”

Shaw said catcalling is not only disrespectful, gross and irritating; it’s scary, too. “You don’t know if these people are going to grab you.”

***

Catcalling is currently legal in Quebec. However, the province’s Green Party wants to change that. Last month, the party announced on social media their desire to make catcalling a ticketable offence. Such legislation would allow a police officer to issue a ticket to someone who is caught or reported to have been yelling derogatory, sexual and other verbal harassments on the street.

The Green Party of Quebec’s post on social media was a way of gaging public opinion and hearing different perspectives, since the proposal is in its early stages. According to the party’s leader, Alex Tyrrell, making catcalling illegal would not require modifying the Criminal Code. Instead, it would be a non-criminal infraction with a fine that would increase for repeat offenders, similar to jaywalking.

“Although the Criminal Code can address intense situations of criminal harassment, it’s not very well equipped to deal with the everyday situations,” Tyrrell said, adding that it is a challenge to reprimand a catcalling perpetrator in criminal court. “We’re trying to address it at a lower level.”

According to Tyrrell, a law against catcalling would be easier to enforce as its own infraction, rather than falling under the scope of criminal harassment. “More people would be sanctioned for their inappropriate behaviour, but it wouldn’t be tying up the court system […] with a whole bunch of criminal trials,” he said. Additionally, people would be less likely to contest fines if they were not considered criminal offences, Tyrrell added.

While the law would not ensure every catcaller is caught, Tyrrell said he is confident that giving police officers the ability to ticket the incidents they witness would help. “There’s an increased chance that people who are frequently engaging in this kind of behaviour will be sanctioned,” he said.

On Tyrrell’s personal Facebook page, where the idea for the legislation was first publicized, some users posted comments questioning the likelihood that the law could pass. Others said the focus should be on educating the public about why catcalling is wrong and encouraged women to stand up to catcallers.

“It’s not reasonable to expect people to confront their aggressors. Why does the burden fall on the victim?” Tyrrell said in response to such comments. “It’s really up to the police to enforce the laws, to sanction this kind of inappropriate behaviour. It’s really kind of strange how people put the responsibility back on the victim so quickly in certain cases.”

There are also concerns this legislation could infringe on Canadian free speech laws, and tickets for catcalling might be contested on these grounds. “They have the right to argue these points in front of a judge,” Tyrrell said. However, he added that if catcalling were considered hate speech, it would not be tolerated in Canada. “If someone was systematically yelling racial slurs at minority groups and encouraging others to do the same, it could be counted as hate speech. The same should apply to people who systematically catcall women because of their gender,” he argued.

In addition to objectifying women based on their gender, catcalling can be racialized as well—something Dina El Sabbagh is quite familiar with. “I feel, often, a catcall will linger when they recognize features in my face, hair and skin,” said the Concordia studio arts student. “Objectifying minorities sheds a different light on the issue of catcalling.”

According to El Sabbagh, men who catcall her often ask where she is from and attempt to speak the language they associate with her appearance. She said this behaviour fetishizes her race and reduces her identity to the desires of the perpetrator. “Object and use of object, ultimately, is what is at the root of catcalling.”

France is the most recent nation to discuss making catcalling illegal, in a proposal put forward to the government in October 2017. Before it can be sent to Parliament to be voted on, however, the proposal needs to be approved by France’s minister of justice, the secretary of state for equality and the minister of the interior. The law would impose a fine on anyone caught making loud, crude comments about a woman’s appearance or body.

According to Marie Balaguy, the political organizer for the Green Party of Quebec, if catcalling were considered an offence, it would make this type of behaviour officially inappropriate. Even if the law is difficult to enforce, she said, it would make people think twice about catcalling.

“I don’t think people realize how much they’re affected by what is declared legal and what is declared illegal,” Balaguy said. Not only does she think a law would change how people view catcalling, but Balaguy said making it a ticketable offence would be a tool of empowerment for women.

Teague O’Meara, a Concordia student in women’s studies, said she vividly remembers the first time she was catcalled. She was about 11 or 12, and ran home in fear of being physically harmed. At the time, O’Meara didn’t know what catcalling was, how to handle the situation or what to expect from the perpetrator.

“I started to get used to it,” she said. “When you get used to it, you’re less likely to comment.” O’Meara added that, when she does speak up against a catcall, she is often harassed even more and called a bitch.

***

There hasn’t been a single night when Danielle Gasher, a Concordia journalism student, wasn’t catcalled as she walked home from her bartending job in the Plateau at 4 a.m. Whether it’s small remarks or more derogatory, sexual comments, she describes catcalling as “a microaggression and a violation of space.”

When she first had to deal with catcalling, Gasher said she felt timid, scared and would try to ignore the comments. Now, she describes herself as more confident and assertive towards catcallers. This behaviour also angers her much more now, which has lead to potentially dangerous situations.

Gasher’s most recent encounter took place last weekend, while she was walking home from work with a female co-worker along St-Laurent Boulevard around 4:30 a.m. “A car with four men stopped, and one of them rolled down his window to try to pick us up,” Gasher said. “I lost it. I started yelling at him, screaming, ‘Don’t talk to me’ and insulting him.”

“I wanted to humiliate him in front of his friends the same way I have felt violated and humiliated over and over again for years,” she said. The car came to a halt further up the street, Gasher recounted, and the men continued to insult the women and threatened to beat them up. “Luckily, it didn’t happen,” Gasher said. “The streets were empty so, when I think back on it, it probably wasn’t a good idea.”

Gasher said her male co-workers don’t understand what catcalling is like when they tell her to just ignore the behaviour. “They have never been in that position of objectification—the constant male gaze,” she said. “It’s socially accepted harassment, [and] if we keep normalizing it, it’s never going to go away.”

Gasher said that, while she is unsure “throwing a ticket at the problem” will reduce catcalling entirely, she supports the legislation’s attempt to legitimize the behaviour as a inappropriate.

According to Tyrrell, this legislation would be just one component of the Green Party of Quebec’s effort to tackle the province’s rape culture.

“If the Green Party was running the province, there would be a number of initiatives that would be in place,” he said. Among these initiatives would be the implementation of public awareness campaigns about sexual assault, harassment, rape culture and catcalling, as well as improved sexual education in elementary schools.

Balaguy added that a law prohibiting catcalling is a short-term solution. “In an ideal world, that law would become obsolete because catcalling would just not be a thing anymore,” she said. In order to achieve this reality, Balaguy said, a long-term public education plan is necessary to reshape society’s perception of catcalling.

Despite the activist party’s attempt to make the condemnation of catcalling commonplace, Tyrrell said they are “operating in very difficult circumstances,” in reference to a male-dominated provincial government. Out of 125 members in Quebec’s National Assembly, only 37 are women, or just under 30 per cent, according to the National Assembly of Quebec’s official website. In comparison, more than 50 per cent of the Quebec population in female.

However, Tyrrell noted that, since the 2017 municipal elections, there are now many more women holding mayoral positions in Montreal (seven of the 18).

“Maybe they would be interested in adopting [this legislation] at the municipal level,” he said.

The Green Party currently does not hold any seats in the National Assembly. “If we don’t win the election, then we’ll try to pressure other parties to follow,” Tyrrell said, referring the upcoming Oct. 1 provincial election. “Hopefully it will be picked up by progressive parties,” Balaguy added.

According to Tyrrell, the party will be running a series of six consultations in the coming weeks with current party members to determine and finalize the party’s official platform. Catcalling will be among the social justice topics discussed, and the party will release a finalized platform in May, Tyrrell said. “So far, the response to this proposition has been overwhelmingly positive.”

Graphics by Zeze Le Lin