A look into Karrie Fransman’s graphic novel, Death of the Artist

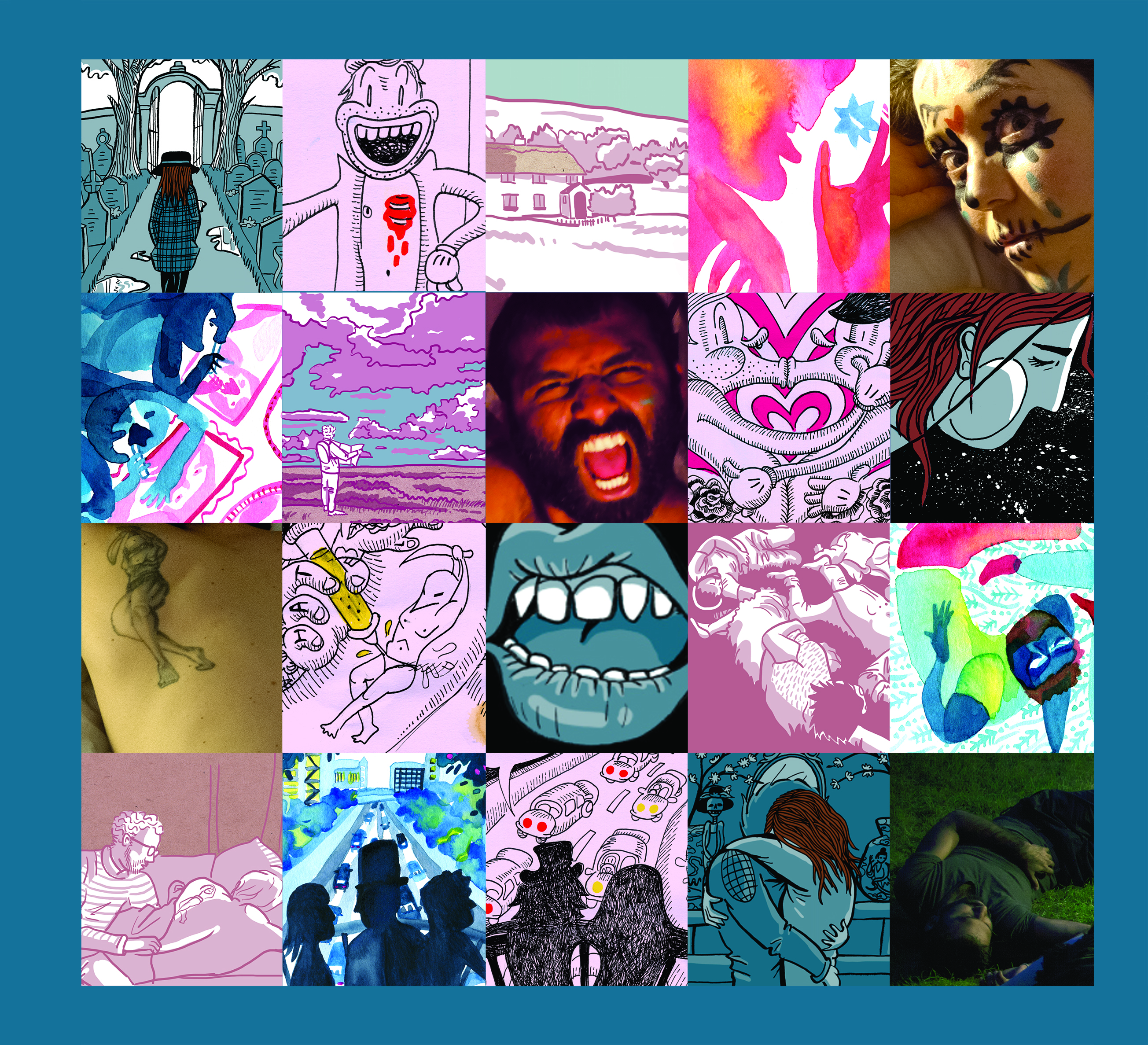

Artists often become so concerned with life they stop living; so preoccupied with their work they stop creating—we human beings become so involved in being stars that we just stop being. Fransman deals with these themes critically in her second graphic novel called Death of the Artist, in which she concocts a story using various platforms such as watercolours, digital art, photography, and collage. It synergistically becomes a thrilling chronology of what it’s like to be unloved, unappreciated and underfunded while trying to make ends meet on the banks of the Seine river.

It is a commonly-held perception that artists are more famous when they are dead. As Karrie Fransman, the author of the graphic novel Death of the Artist told The Concordian, “perhaps people can freely project their own ideas on art once those pesky artists are dead and gone.”

That’s the downfall to stardom—throughout their careers, artists become overly concerned with visions of success and fame, and reaching their ideal often clouds their actions.

“We love to watch stars crash and burn and gather around them like sadistic moths!” Fransman said. “I think as a society we are obsessed with creativity and self destruction.”

On the surface, the story is simple. Five former friends: a painter and poet, a graphic design student, a comic creator, an amateur photographer, and a zine maker plan a reunion 10 years after meeting in college. The purpose of their reunion is to reinvigorate their inner artists by compiling an anthology. They spend a week tinged by nostalgia trying to rekindle the artistic drive of their youth by “creating a toxic environment in the name of creating,” as Fransman puts it. Throughout this journey, she examines universal themes of life and death, reflecting on how age conquers character, and how the effort to revive our youth can in turn destroy growth.

What’s the catch? It’s five narrators, five different styles, all written by one author. When asked what her inspiration for this was, she replied, “I’m not that great at collaborating in all honesty. But then I said ‘wouldn’t it be great to do a whole comics anthology pretending to be different artists?’” With this challenge in mind, Fransman takes the graphic novel into an entirely new realm.

Fransman’s inspiration stems from a T.S. Eliot quote in Four Quartets: “In my beginning is my end.” “All rising will result in falling, all coming together results in parting, the world moves in cycles, it’s very Buddhist,” she said.

These three words, ‘death of artist,’ carry layers of depth and an array of symbols and motifs. Fransman constructs a multiple-entendre narrative that sneaks in the idea of death in the least expected instances. When asked to explain her theme, she said, “there’s the theme of the anthology, the death of the group’s youth, the actual death, the petites morts, and the reference to the Roland Barthes essay “Death of the Author,’” all of which Fransman adopts by being one of the characters and fragmenting herself into five versions of “Karrie” seen through five different sets of eyes. When asked where she lies in the midst of this spiral, Fransman responded that “I become an unreliable narrator and am thus kind of killed off.”

It’s difficult for the reader not to develop a philosophical outlook on this novel. The title itself is burdened with an existential undertone. It’s even harder to resist wondering about the mysteries that surround Fransman’s authorial intent. Reading this novel is like entering a void where you live through the characters, feel their grief, and even see some of them die along the way.

The novel is beautiful in that it offers each reader an opportunity to deconstruct the events and characters. Fransman successfully exploits the plasticity of the comic medium while simultaneously addressing important existential realities suffered by the “self-centered aggression of artists’ hedonism.” What is found is an excellent manipulation of both style and substance, a powerful grasp on the unique potential of the comic form. There is no single way of interpreting this novel—the closer you read it, the more complex it becomes. The five different perspectives have entirely different flavours, yet the whole novel illustrates a particular sense of everlasting curiosity.

Fransman ceases to intentionally dictate the mood, leaving the reader to perceive it as they will. Feelings of empathy are automatically stripped away as she cleverly offers space for subjective interpretation while maintaining an objective relationship with the characters.

“The artists are a pretty cruel bunch, aren’t they? Interestingly, I seem to never want to write likeable characters,” she says.

To create multiple voices, Fransman says she was inspired by various literary sources such as Virginia Woolf’s The Waves, Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, and William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying. As popular as having a multitude of characters’ voices is in literature, it has rarely been experimented through comics. “That’s why I love this medium. There’s still so much unchartered territory,” Fransman said.

The novel may initially appear to celebrate decadent behaviour and self-destructiveness. Nevertheless, towards the end, the reader will notice how the hubris behind their creativity backfires. Everything comes at a price. For Fransman, this price comes in the form of her artwork. It becomes more structural, morbid, and toxic, both artistically and narratively. The colourful palette is relinquished while shades of black, white, and grey gradually take over and become the main orchestrators of the narrative. A dark cloud casts over the too-good-to-be-true sunshine. This is where the title comes to life and where Karrie’s reality kicks in. The artists keep eating the lotus, but eventually one of them gets poisoned. Fransman wraps her novel rhetorically, questioning the extent to which artists should feed their Dionysian egos. While these characters were gradually murdering their inner artists, Fransman was busy reinvigorating her own.

To find out more about Karrie Fransman, visit her website www.karriefransman.com.