Indigenous artists explore their Indigeneity and navigate colonialism in Braiding Our Stories

The Cree are storytellers, like many other First Nations. Their worldview is lived through wahkohtowin (kinship) with the Land. “We continue to tell our stories, as best we can, as beacons for our relations to find their way home, so they too can live miyo pimâtisiwin—the good life,” wrote Melanie Lefebvre for her oral history class, which culminated in her short film, I Will Return.

A Cree/Métis mother, Lefebvre is a Masters student in the individualised graduate program focusing on Indigenous studies and is among the 12 artists navigating Indigeneity in Braiding Our Stories, an exhibition at the VAV gallery. In these many stories, Lefebvre’s short film I Will Return explores aspects of the Plains Cree worldview through her relationship with her daughter, Anne. Narrating Cree teachings, Anne exchanges and shares ideas of kinship relations within time and place.

In conjunction with First Voices Week and the VAV Gallery, the exhibition is curated by a graduate and undergraduate duo, Juliet Mackie (Métis, Cree, Dene and Gwichin from Fort Chipewayan, Alberta) and Alexandra Nordstrom (Plains Cree, Euro-Canadian, member of the Poundmaker Cree Nation, Treaty Six Territory, Saskatchewan). Selected by the Indigenous Art Research Group and guided by Dr. Heather Igloliorte, Mackie and Nordstrom have been braiding artists’ stories since November 2018.

The name, Braiding Our Stories, alludes to the curators’ own experiences navigating their identities and resonates with the experiences of the artists they’ve chosen to support.

Craig Commanda comes to terms with their heritage though playing the guitar, juxtaposing contemporary and traditional Indigenous music.

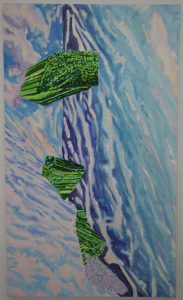

Dion Smith-Dokkie creates utopic spaces by drawing on cartography, mapmaking and satellite imaging technologies to talk about their perceptions of space and place in northeast British Columbia. As a member of West Moberly First Nations, a community located in the Peace Region of British Columbia, their experience with traditional land use studies forms the basis of these works.

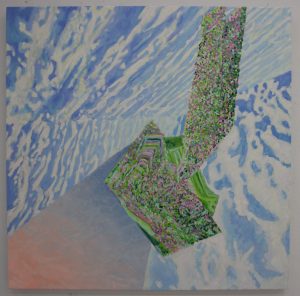

The exhibition welcomes Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples into the space with Creation, a large, six-by-four-foot painting by art education student from Akwesasne, ON, Destiny Thomas. Creation illustrates the Mohawk Creation Story of Turtle Island (North America) and the birth of Mother Earth.

After Sky Woman landed on Turtle Island, she gave birth to a daughter. She was warned to never walk West, but she ignored her mother. The daughter walked West and saw a man figure. Due to shock, she fainted. When she woke, she had two arrows resting in an ‘X’ on her belly and was pregnant with twins. While in the womb, these twins would argue. When it came time to giving birth, the Right-twin was born the proper way, while the Left-twin was born through his mothers armpit, killing her. Sky Woman became the Grandmother to the twins and raised them herself. Together, they buried the daughter and from her soil came corn, beans and squash, these are known as the Three Sisters. From her heart, grew tobacco and from her feet, grew strawberries. Along with her burial, came the daughters name, Mother Earth. With time, the brothers would create humans and other beings. They were never in agreement, so when one created something good, the other would spite his creation. Predator and prey, sickness and medicine, night and day… This is recognized as the perfect balance of good and evil.

(Text by Destiny Thomas)

While painting, Thomas thought of how the universe has come to be. “Everyone has their own interpretations: aliens, god, some superior being,” she revealed. “I tried to pry away from the Creation Story that I was constantly told as a child. But as I thought about it, it became the Mohawk connection or interpretation to all creation stories.”

Next to it is To My Dearest Friend, a much smaller beaded work dedicated to Thomas’s childhood friend, who passed away in 2018. In making this piece, Thomas found herself needing to take many breaks. “When doing beadwork, how you’re feeling shows […] If you’re tense and angry, the work will be tight and wavy. If you’re happy. the work will be slightly loose. If you’re content, the work almost always comes out perfectly,” explained the artist, “while beading the flowers, you can tell where the happy, sad, and content moments were in my work.”

To My Dearest Friend is meant to be looked at closely and from different angles—the artist’s process is parallel to that of art therapy. With fluid and controlled movements, she makes herself aware of her breathing throughout the entire process. The bead work allowed Thomas to grieve and come to terms with how she was feeling. To My Dearest Friend became the perfect vessel to symbolise the grieving process.

Mackie, Nordstrom, Lefebvre, Thomas, and all the artists exhibiting in Braiding Our Stories have one thing in common; they are Indigenous artists. To some, this may bring visions of “traditional” Indigenous ways of making, beading, basketry, braiding sweetgrass… but Indigenous Art is more than that; Indigenous Art, which is capitalized to express the significance of the genre, doesn’t have to look traditional. “Indigenous Art means that it was made by Indigenous people,” explained Mackie. “There is no such thing as ‘not Indigenous enough.’”

First Voices Week is celebrating its fifth edition with a week’s worth of lectures, workshops, panels and discussions. Visit their Facebook event page for more information.

Braiding Our Stories will be open at the VAV Gallery until Feb. 15, Monday to Friday from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m.

For more information on how to be a true Indigenous ally, read the toolkit created by Dakota Swiftwolfe and Leilani Shaw of the Montreal Urban Aboriginal Community Strategy Network.