Unearth the historic roots running throughout the island of Tiohtiá:ke

Scientific historians speculate that it was Aristotle who first decided all living things could be divided into two domains: plants and animals. While biological taxonomy is a touch more complicated these days, the conceptual divide between flora and fauna remains central to western scientific thinking about nature.

But here’s the thing: a key assumption of that conceptual divide is that animals are apperceptive, while plants are not. Plants don’t feel pain, while animals do. Yet, over the past few decades, there have been a number of startling studies—such as one led by Antonio Scialdone at the U.K.’s John Innes Centre, which found that Arabidopsis thaliana were “capable of doing some complex arithmetic to prevent starvation at night.” These findings, as well as others, suggest this divide may not be as clear cut as it seems.

Trees, in particular, are known to have strangely sentient qualities about them. The belief that trees have some kind of innate intelligent life has been with us for millennia, as Cambridge professor Stanley Arthur Cook wrote in the 1911 edition of Encyclopædia Britannica. So, it is not surprising that trees are cited as having spiritual properties in many sacred traditions.

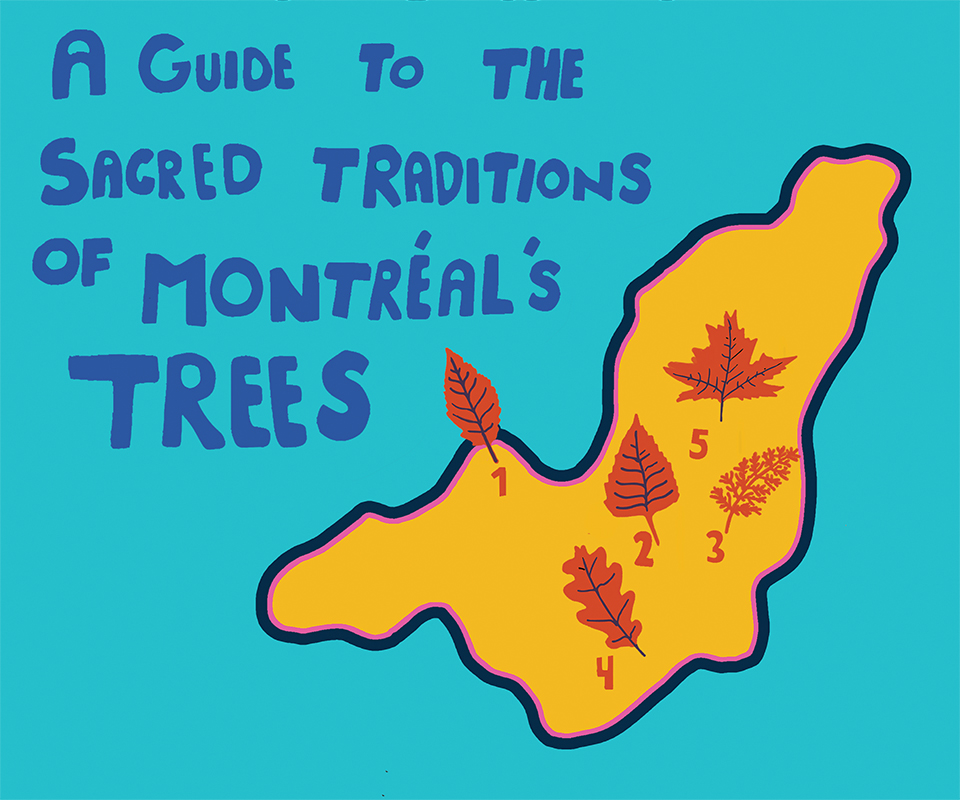

The Concordian teamed up with the Concordia Multi-faith and Spirituality Centre to create this guide to the sacred traditions associated with the trees found on the island of Tiohtiá:ke/Montréal, unceded Indigenous territory of the Kanien’kehá:ka Nation.

You can use the provided map to find locations where these trees grow, and the leaf graphics to help identify specific species. For each one, we mention which aspect of life it is supposed to help with, from prosperity to fertility. If you’re struggling with something, why not try meditating on it under one of the trees associated with your problem?

1. Rapides du Cheval Blanc Park: Ash tree

According to the Oxford Dictionary of Celtic Mythology, the Ash tree was very important to the ancient druids of Briton, and had a prominent place in Celtic culture. It was considered the female partner of the Father Tree, the Oak. The Celts valued Ash for its healing and enchantment properties. The Indigenous peoples of the Great Lakes region have also had a long connection to the Ash tree, according to Nicholas J. Reo from Michigan State University. Within these communities, though, it is valued less for it’s spiritual properties and more as a construction resource, particularly for baskets and snowshoes. However, there is a tradition within the Wabanaki Confederacy that maintains that humans were first created from Black Ash trees, according to Native Languages of the Americas, a non-profit organization dedicated to preserving and promoting Indigenous languages of the western hemisphere.

2. Corner of St. Sulpice and Picket Roads: Birch tree

According to Trees for Life, Scotland’s leading conservation volunteering charity, in parts of Europe the Birch tree is linked to fertility, healing magic, new beginnings and purification. This is likely because its seeds can thrive in extremely inhospitable environments, so they’re usually the first trees to grow again on land that has been razed. Through their resiliency, they set up the new ecosystem for the slow-growers like Oak and Beech. In some Ojibwe and Chippewa communities, Birch bark is thought of as a sacred gift, and was sometimes used in ceremonial wrapping of the deceased for burial, according to Dr. Kelly S. Meier, the Senior Director of Institutional Diversity at Minnesota State University. In fact, Birch bark does have medicinal properties for pain relief, and birch leaves can be used for treating arthritis, according to WebMD.

3. Corner of Guy Street and Argyle Avenue: Cedar tree

According to the Indigenous Studies department at the University of British Columbia, in Ojibwe traditions, the Cedar tree is associated with cleansing, protection and prosperity. It is thought of as the most sacred tree among some Indigenous communities. The west coast Indigenous peoples consider the Red Cedar to be the “tree of life” and believe that it plays a key role in nurturing the mind, body and soul. A prayer of respect is recited prior to any part of the tree being harvested. This is because of Cedar’s ubiquitous use in all parts of northwest Indigenous peoples’ lives, including canoes, clothing, cooking utensils, medicines, ceremonial masks and more, according to The Canadian Encyclopedia.

4. Raymond Park: Oak tree

For many Indigenous tribes of east and mid-eastern North America, Oak is a medicine tree, connected with strength and protection, according to Native Languages of the Americas. Individual Oaks are known for their tremendous size and longevity. According to Indigenous tradition, the location of Oak trees often serve as spiritual and civic centres for important gatherings. In Celtic lore, the Oak is regarded as the holiest of holy trees, according to the Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids. The ancient Greeks and Romans also associated the Oak with their highest gods—Zeus and Jupiter respectively. Even the Norse associated it with Thor, their god of thunder. The Oak tree is the ultimate spiritual symbol of strength and endurance.

5. Wilfrid Laurier Park: Maple tree

Maple syrup was known and valued by Indigenous peoples of the Eastern Woodlands, according to The Canadian Encyclopedia, long before the arrival of European settlers. This tree is so central to some Indigenous cultures that the explanation of the origin of maple syrup production figures into their story about when the Creator made earth world itself. In many North American Indigenous legends, maple syrup originally comes out of the maple tree already edible.

However, at some point, an intervening trickster god—whose name differs from community to community—forces people to process the sap if they want the sweet reward. According to Indian Country Wisconsin, in Anishinaabe legend the god’s name is Wenebojo, but in Abenaki legend he’s named Gluskabe. The maple tree is also seen as a tree of tolerance and gentleness in many Indigenous traditions. It is also the preferred source of ‘talking sticks’, a tool used during council meetings to indicate whose turn it is to speak.

The Concordia Multi-faith and Spirituality Centre runs a series of field-trips every school year to various sacred sites. For more information about this year’s outings contact the centre: [email protected]

Feature graphic by @spooky_soda.