Exploring freedom of speech and censorship within Concordia

As academics, journalists and curators of the public sphere, knowing when to stand by your work is as important as being accountable for it. Journalists in particular carry the responsibility of disseminating information, and, as a result, are rightfully held under constant scrutiny for the content they publish. The same goes for The Concordian, where, throughout its existence, there have been a few instances of backlash to content we’ve published.

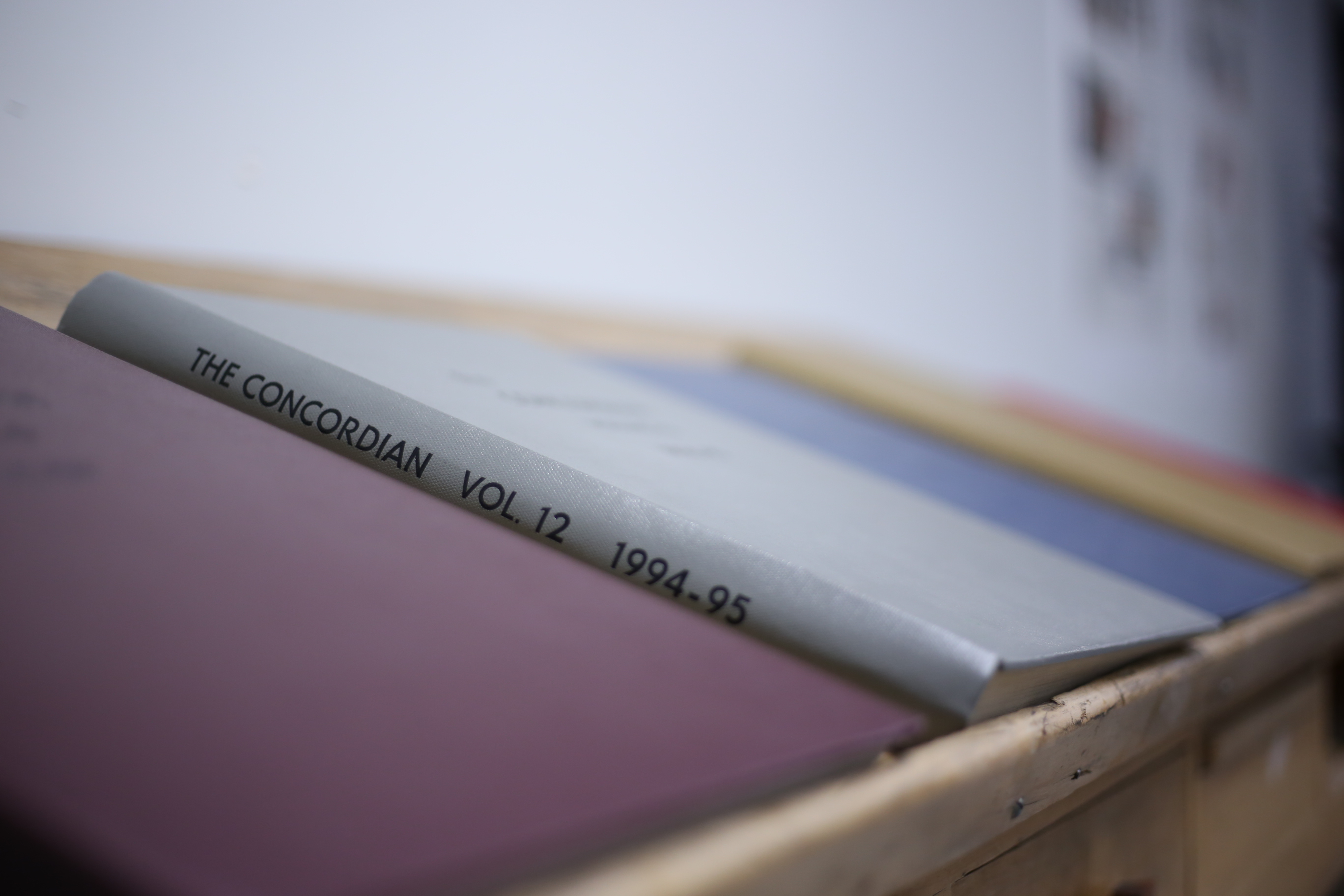

Throughout the mid-90s, The Other Side was a column frequently published in The Concordian by then-journalism student, Elena McLeod. On Nov. 2 1994, the column featured a satirical article written by Mark Rollins, an alias adopted by McLeod, taking on the perspective of sexist male-chauvinists she frequently encountered on campus.

McLeod’s column was raunchy yet progressive when you read between the lines, at least for the mid-90s. It opens with: “I love breasts… Breasts of all dimensions, colour and texture. I love ‘em if they salute the sun or kiss the ground… I’m not ashamed to admit that hooters preoccupy my thoughts 24 hours a day,” writes Rollins. The column goes on to reference a GUESS ad: “[…] everytime I saw Anna Nicole Smith hawking Guess Jeans [sic], I’d blow my load… I swear, these ads should come with a handy Kleenex dispenser,” writes Rollins.

Satire, when done correctly, can be a great way to comment on complex issues by poignantly revealing the power dynamics behind the story. In The Other Side, satire was used as a way to reveal how ludicrous the hypersexualization of the female body and conforming to the male gaze is. McLeod, a.k.a. Rollins, sought to comment on this hypersexualization by using nearly every ‘locker-room’ way of talking about breasts, to the extent that it could not be anything but satire.

However, satires can often miss their intended mark, whatever that may be. Think back to 2015, when The Beaverton published and quickly retracted their absolutely appalling article after Ashley Callingbull, from the Enoch Cree Nation in Alberta, won Mrs. Universe. The Beaverton published a headline that, as they later stated in their apology, was meant to “call out the media for their failure to properly cover missing and murdered [Indigenous] women.” However, while some say they understood the twisted truth behind the headline, many, including some Indigenous advocates, did not see the humour or value in publishing such a serious topic under the guise of humour. When satires aren’t published in complete distaste, they can often be interpreted literally, which leads to a separate slew of issues.

As one could imagine, not every student on campus understood that The Other Side was a satire. The article’s literal interpretation incited a massive backlash from the student body, and by the following week’s issue on Nov. 9, The Concordian had received heaps of phone messages, letters and faxes (yes, faxes) from enraged students denouncing both the publication and Rollins/McLeod.

Most of these comments were published in the ‘Letters to the Editor’ section, next to a column where McLeod came out as Rollins. On Nov. 16, two weeks after the satire column hit print, and a week after McLeod claimed Rollins’ identity, there was still so much continued backlash from the student body, now enraged at McLeod for publishing the column to begin with.

In lieu of all the backlash, McLeod sat down for an interview with Samaana Siddiqui, then-staff writer from The Concordian, to continue to explain that her intent was to generate a public discussion about the hypersexualization of the female body in a way that was not “shoving women’s issues down people’s throats,” said McLeod. However, for many readers, McLeod’s goals in writing the article did not justify the alleged sexism present in the piece that appeared without context, writes Siddiqui.

The inclusion of McLeod’s article in a student-funded publication then became a debate between free speech and censorship, generating even more letters to the editor, all continuing to denounce The Concordian—some personally attacking McLeod and her sexuality.

According to Siddiqui, a student-run protest was meant to gather outside of The Concordian’s office to demand the return of their levy fees, though the rally never happened. Many Concordia affiliated groups such as the Women’s Centre and the Quebec Public Interest Group circulated a letter to The Concordian’s ad sponsors, encouraging them to sever their partnerships, according to Siddiqui.

The backlash created so many ripple effects, bordering industry blacklisting, that then-Editor-in-Chief Daniel Nemiroff published an editorial on Nov. 23 supporting McLeod and her piece. “If it will help the offended for me to express regret, I’m willing to weep with you,” writes Nemiroff. “I will not, however…censor young writers, or curtail freedom of expression.”

Journalists are held to high standards for their content, and are constantly faced with the threat of backlash, which is all the more immediate given the advent of social media. This scrutiny is completely necessary, which makes finding a suitable balance between validating the opinions of readers and supporting the freedom of expression for writers highly contextual.

Feature photo by Alex Hutchins